Panama: April/May 2018

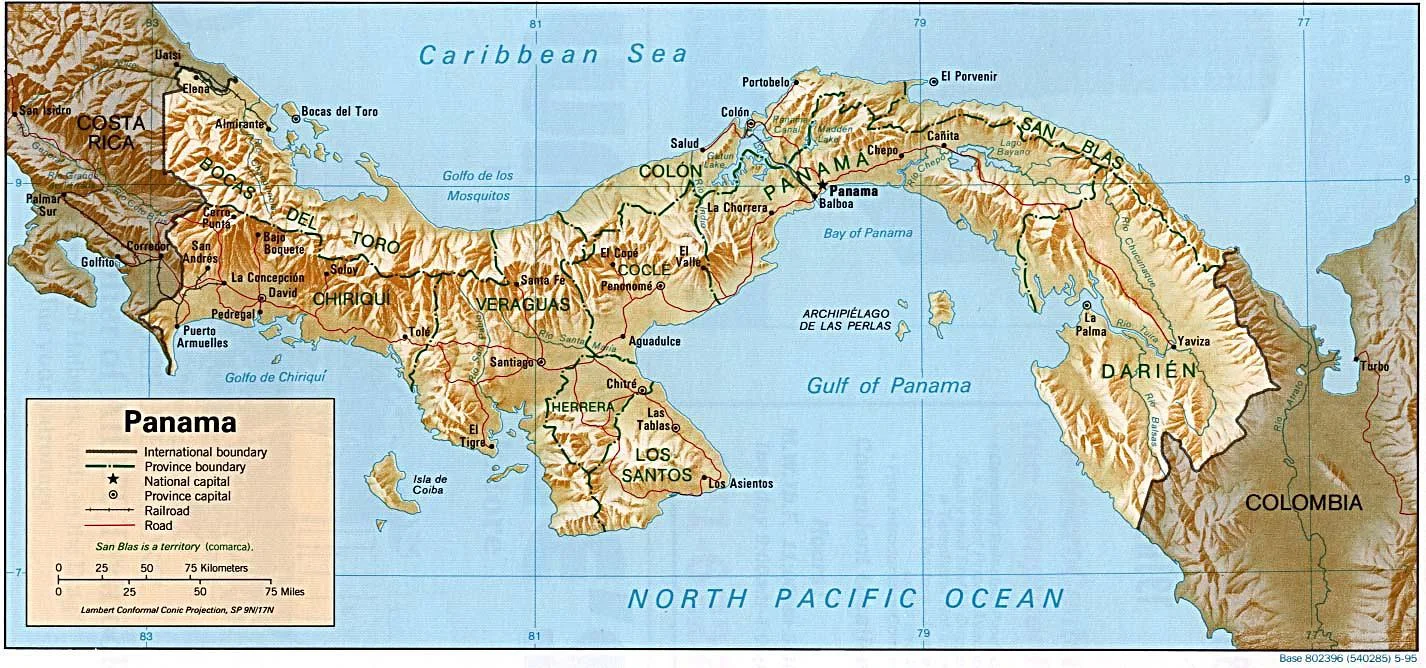

Panama, located in the south of Central America has 75,400 km2 (about the size of Austria) and 4.05 million inhabitants. 40% of its surface are covered by jungle.

Initially part of Colombia, Panama became independent in 1903 when the USA supported separatist forces which were willing to sign a treaty for the construction of the canal under conditions rejected by Colombia. After several decades of military dictatorship parliamentary democracy has been restored in 1989. While Panama is a middle-income country and ranks 54th in GPD per capita there are significant social disparities and approximately a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line.

The capital Panama City and its surrounding areas are home to nearly half of Panama’s population. Historically it was Spain's launching point for the conquest of Peru and later became a key port to transport the wealth extorted in South America to Europe.

Located at the eastern end of the Panama Canal the city today functions as a major international financial and banking place with the reputation of being a tax heaven (recall the “Panama Paper” scandal).

As such Panama City has three different faces, the rich, the poor and the old part. The rich/modern part is dominated by an impressive skyline of skyscrapers and extravagant architecture.

In stark difference to the banking city is the barrio Chorrillos where unemployment and crime rate are high. As walking on foot through that area is not recommended I luckily found a taxi driver willing to drive me through this rough neighborhood. As two of his brothers are “doing business” in Chorrillos he provided me some insight, e.g. that pairs of shoes hanging on power/telephone lines indicate a place where drugs are sold en gros and en detaile. Thousands of people patiently queued in at a place where a popular football player once a month arranges selling of food for half the price.

The old town (called Casco Viejo / Old Quarter) was built in the late 18th century. It currently is in a comprehensive process of renovation.

Street views from the old town: the traditional Panama straw hats; preparing to attend a wedding; street performance and street art.

1519 Panama initially had been built 8 km east of today's old center. After British pirate Henry Morgan with 1,400 men had looted and burnt down the town in 1671 Panama was rebuilt on another place easier to defend. The ruins of Panama Viejo (old Panama) can still be visited.

In Panama City I met an old friend Jose "Cheama" Torralbo. We worked together for UNDP in Somalia 2014/15. Chema now is the UNDP Regional Security Advisor (ai) for Latin America & The Caribbean.

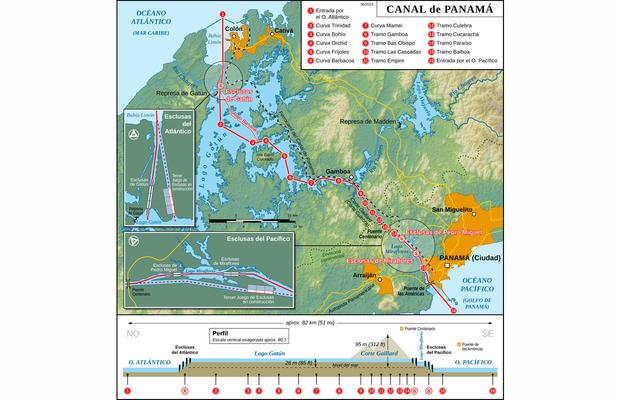

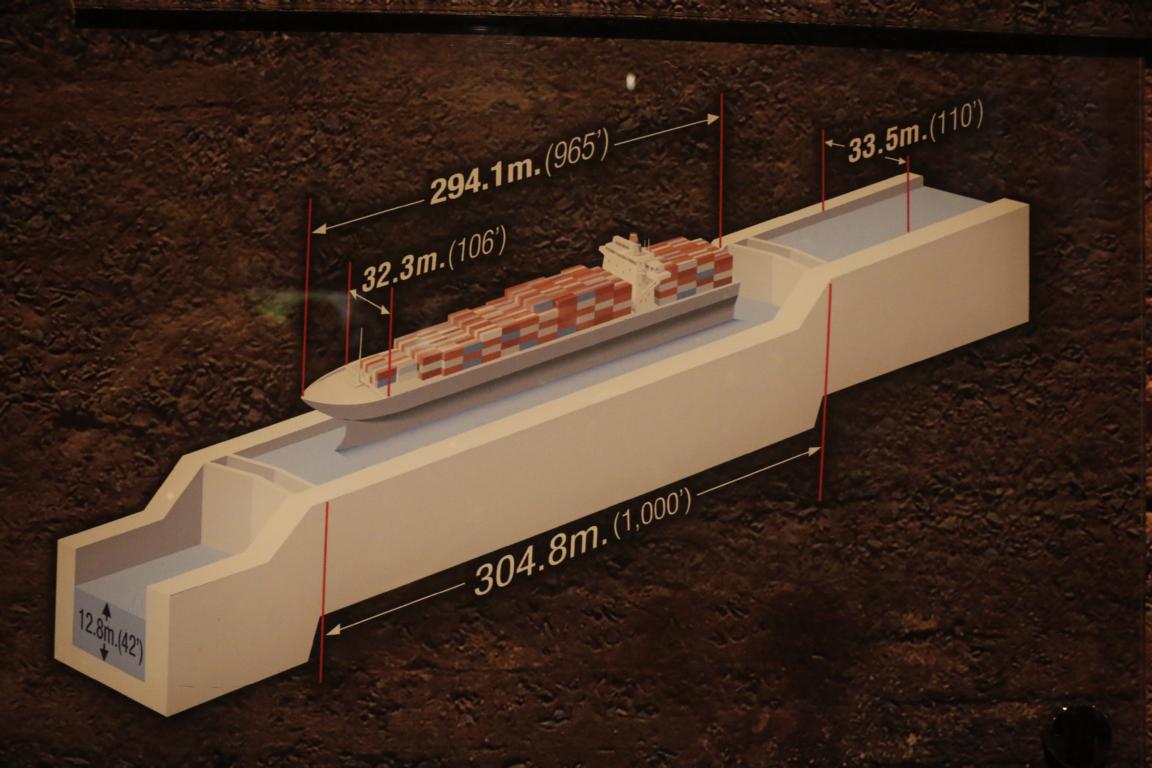

The Panama Canal, an artificial 77 km waterway built between 1880 and 1914 that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean, is Panama’s economic backbone. Some 13,500 ships (35 to 40 a day) pass the canal each year. It takes between 8 to 10 hours to travel through the canal compared with two weeks to go around South America. The canal consists of a system of dams and floodgates which created several artificial lakes enabling ships to cross the isthmus 27 m above sea-level.

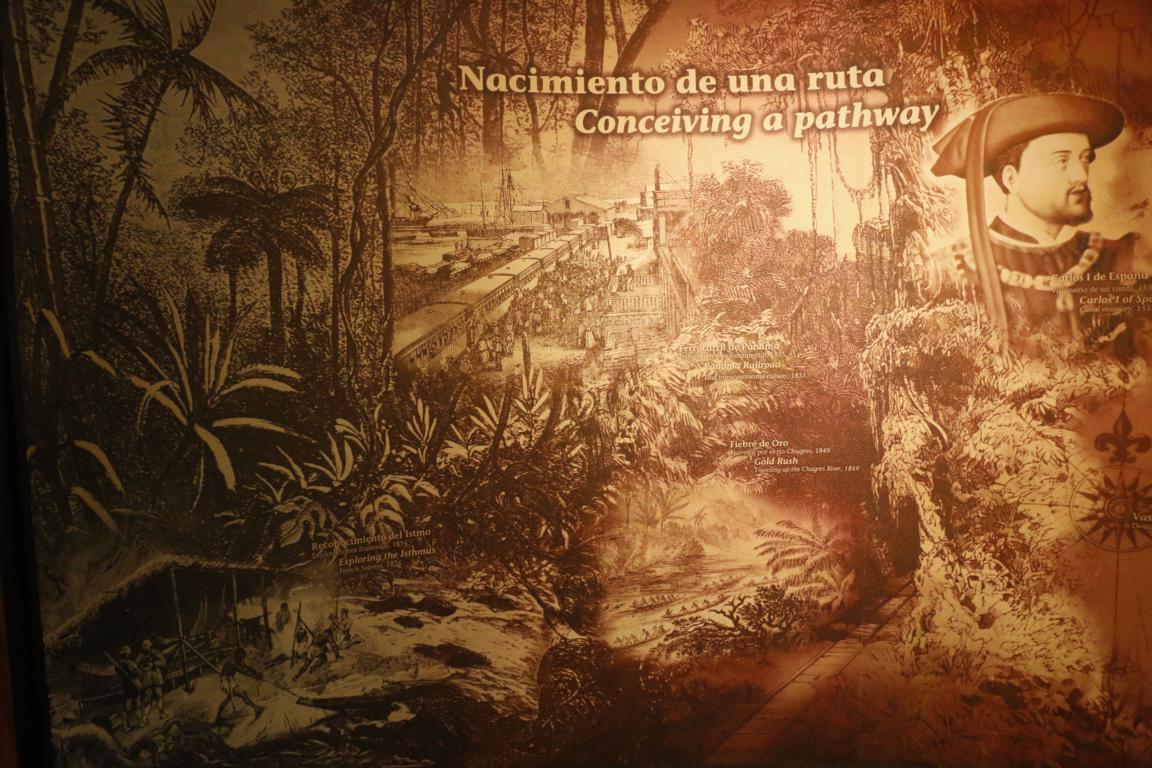

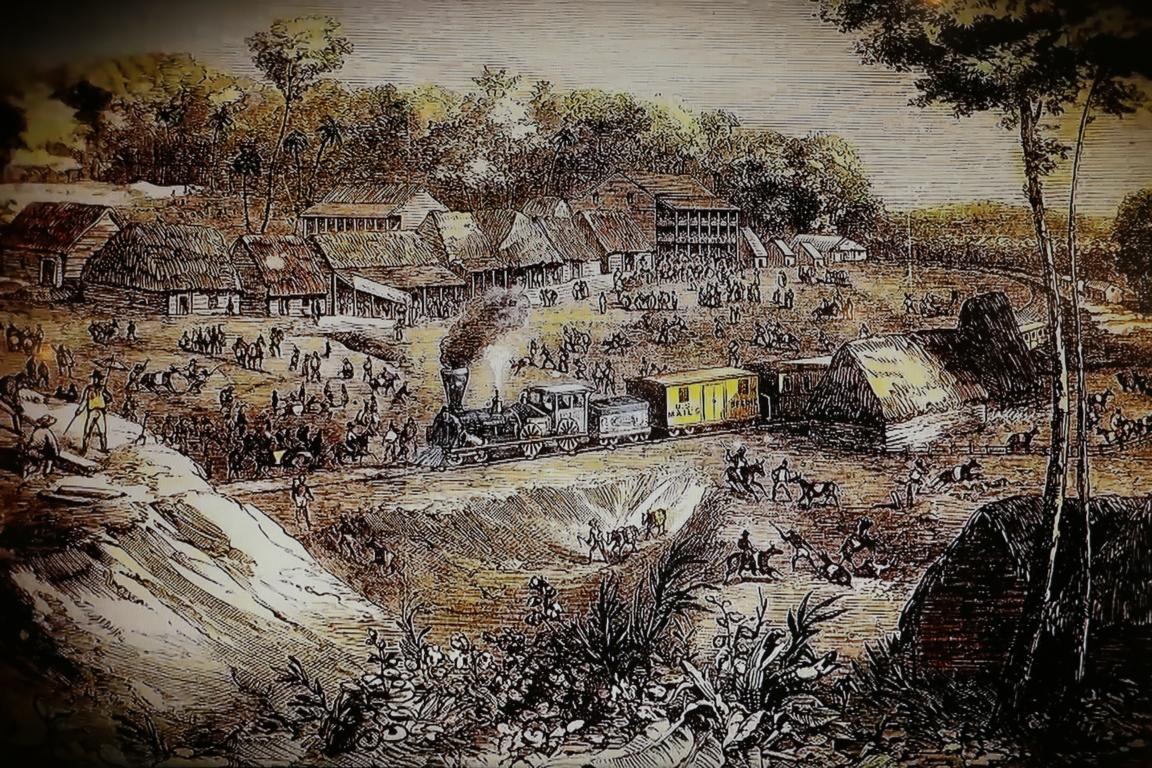

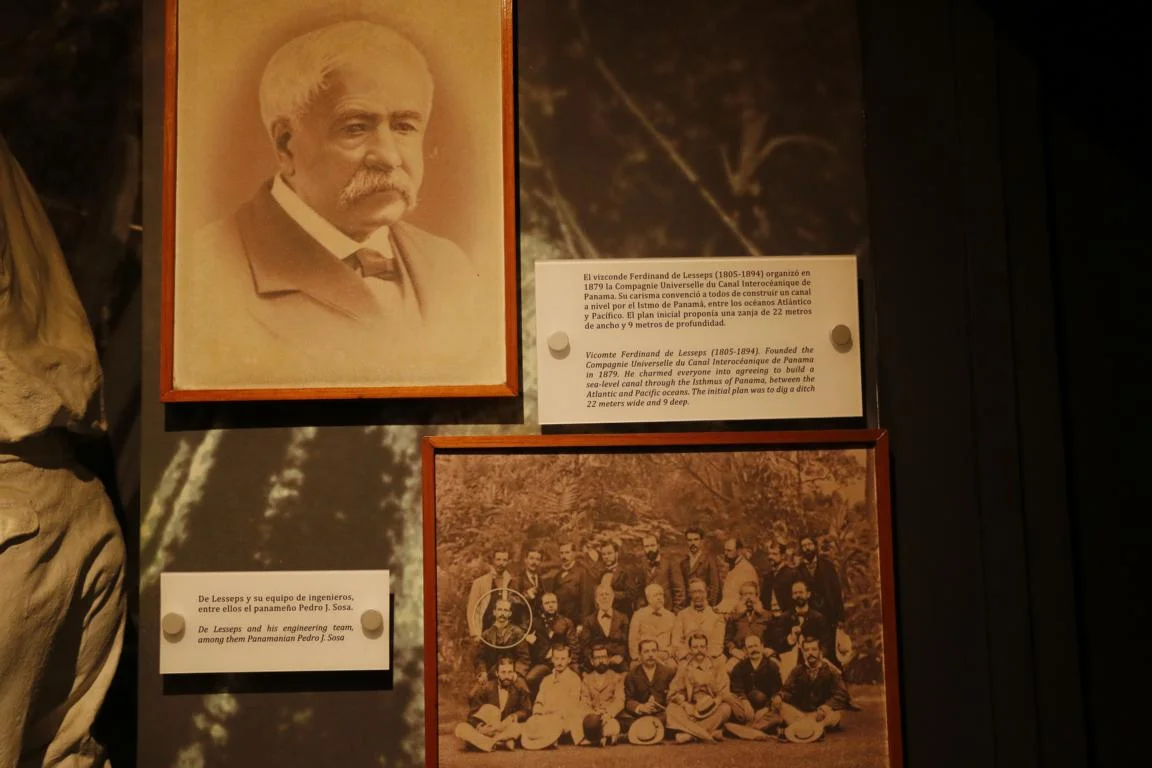

Since the 16th century attempts were made to ease the transport of goods via the isthmus of Panama. In 1855 the first railway line had been finished replacing the old Camino Royal built by Spain to transport goods by mule overland. The first attempts to build a canal were undertaken by the French under Ferdinand de Lesseps (Suez Canal) who planned to construct a sea-level canal. Excavations started in 1880 but eventually had to be abandoned nine years later due to high death tolls (some 20,000 workers died mainly due to diseases), geological problems, misappropriation of funds and lack of capital.

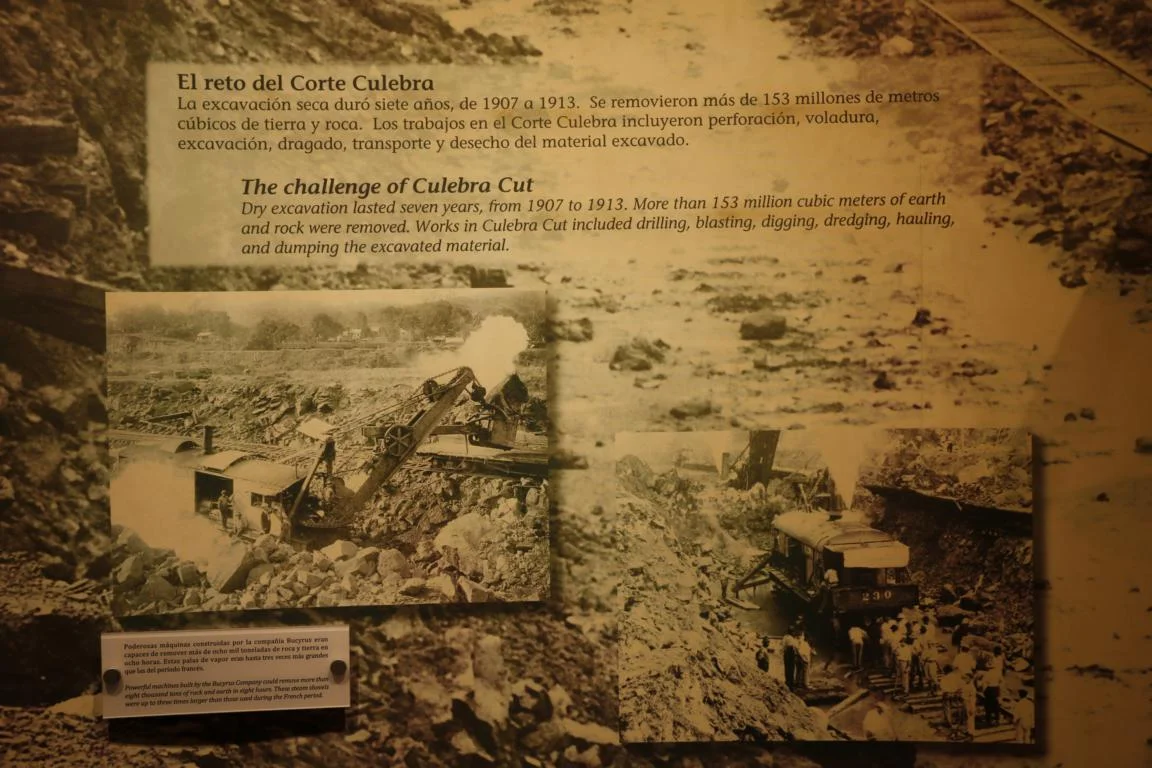

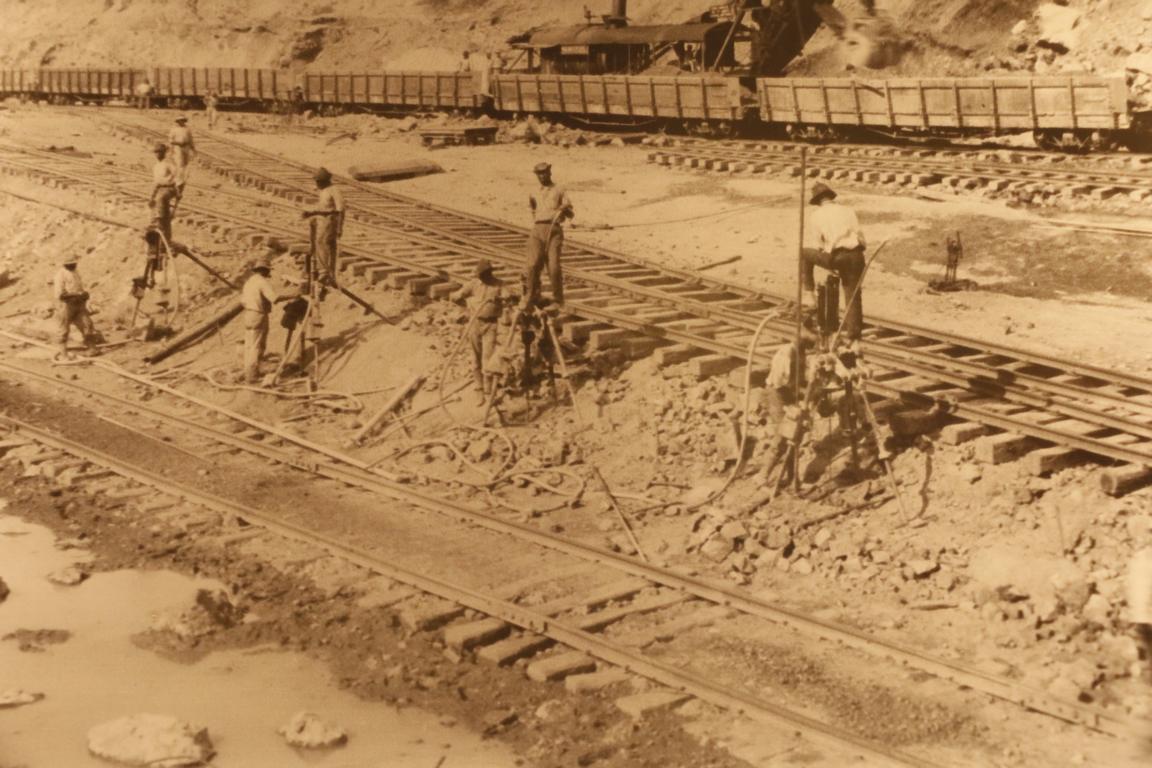

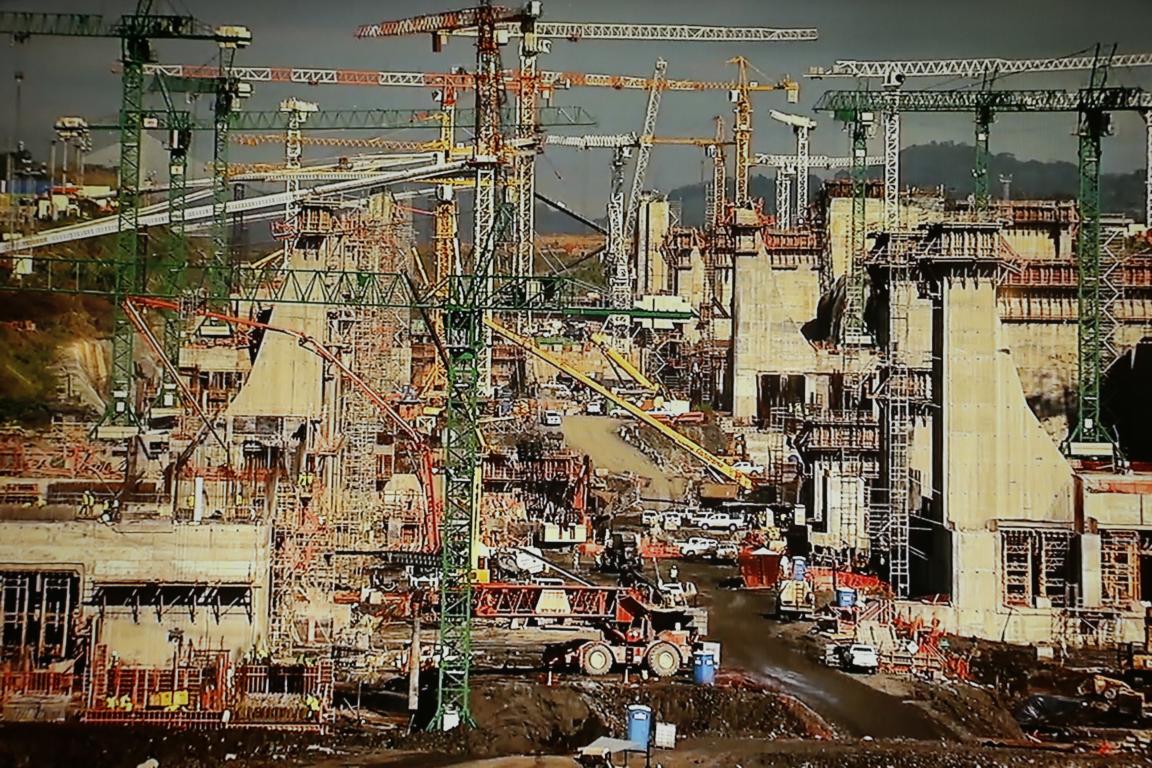

After the USA had supported a separatist movement to secede from Colombia the new Panamanian government conceded extensive rights to the USA to build and manage the canal. Work was completed between 1904 and 1914 constructing a lock-and-lake canal (instead of a sea-level canal). Some 55,000 workers of all parts of the world contributed to the construction (pictures taken from the canal museum)

After decades of tensions the USA in 1999 handed over the sovereignty over the canal to Panama. In order to adapt the canal to the increased size of ships Panama in 2016 completed the construction of additional locks on both sides which doubled the canal’s capacity. The last photo shows the old and the additional new floodgates (pictures taken from the canal museum).

The south-eastern part of Panama comprises of the Darien Region (11,896.5 km2, 50,000 inhabitants) consisting of mountain ranges and swamps covered by primary or secondary rain forest. Beside one central road there are only few other roads. Transport mainly takes place along the many rivers, some navigable only during the rainy season (May until December). Darien is settled by the Embera, the Wounaan and the Kuna who live from agriculture, fishing and hunting. The deeper they are settling in the jungle the more traditional is their lifestyle. It is amazing that some 300 km south-east of the sky scrapers of Panama City there is a completly different world where people in some aspects live the same way as centuries ago.

At the town of Yaviza the Panamericana abruptly ends only to continue some 100 km further south in Colombia creating the so-called Darien Gap. Geological challenges, environmental concerns, resistance by the indigenous tribes and security problems (in particularly on the Colombian side) so far prevented the construction of a road or rail connection between Panama and Colombia. Others claim that the Darien Gap intentionally is kept in order to leave a natural barrier against migration from South America to the USA and to have a sanitary cordon to prevent diseases spreading from south to north. So far only a handful of cars have crossed the Darien Gap in expedition style partly using barges to move the cars up and down the rivers. The first all-land auto crossing was in 1985–87 and it took 741 days to travel 201 km. Motorcyclists more often succeeded to cross the Darien Gap.

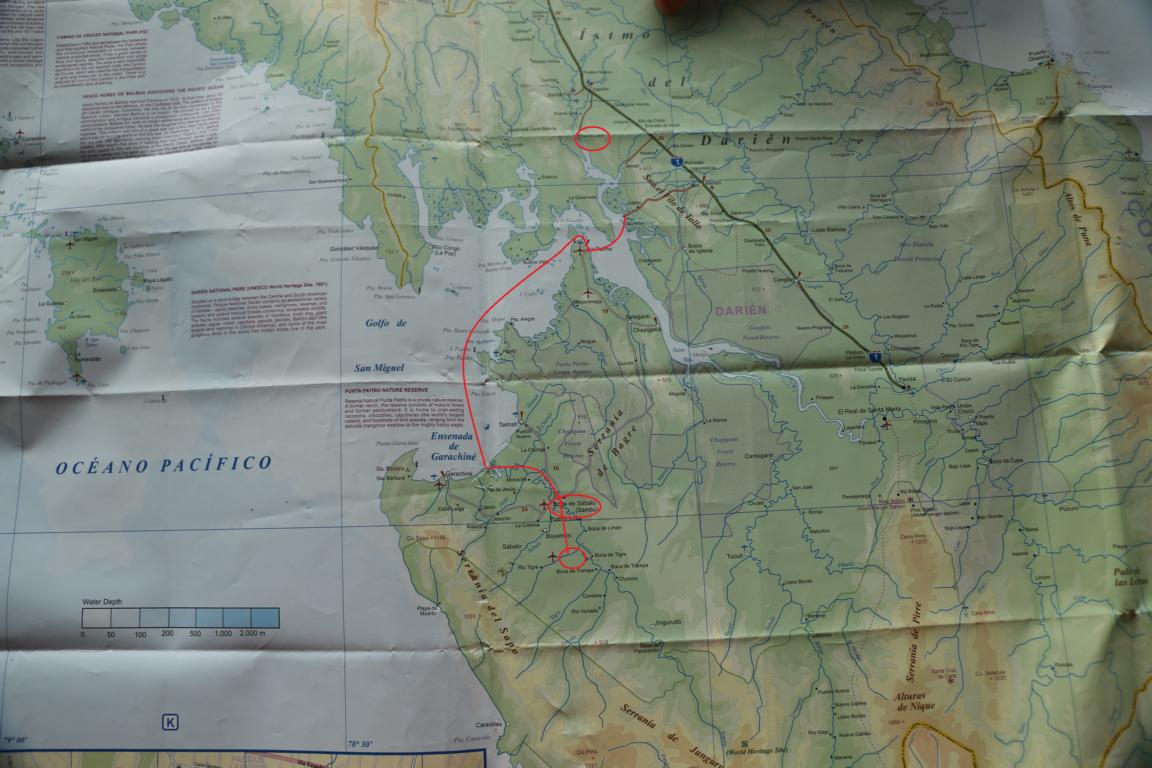

I had the luck to meet Michel Puech a French/Panamanian citizen aged 74 who dedicated half of his life to explore and research the Darien region. He runs a small agency to promote ethno-tourism (www.panamadarien.com ). Together with him I went for a five-day trip to visit several Wounaan and Embera villages.

Our first stop was at Boca de Lara a small Wounaan settlement. Photos show Amalia preparing food in the traditional way using fire resistant leaves.

On one of the hill tops of the surrounding mountains we found the remains of a radar station set up by the US army in 1941 to defend the Panama Canal against possible Japanese attacks.

Animals and plants of the rainforest. One of the plants is particularly outstanding, called Sweet Lips (guess why).

La Palma the capital of the Darien Province can only be reached by boat.

The twin town Sambu / Puerto Indio located on the Sambu river is settled by the Embera tribe.

The Regional Cacique (chieftain) Laziro Caibera took the time to explain me the structure of the indigenous self-administration, the traditional laws applied and the how they manage everyday life. Tereza Changa is a traditional healer and shaman who provides medical assistance to the population based on medicine produced out of plants of the jungle. While Embera are Christians they still believe that evil spirits can cause sicknesses. For serious cases a witch (brucha) is called who lives some two travel-days upstream.

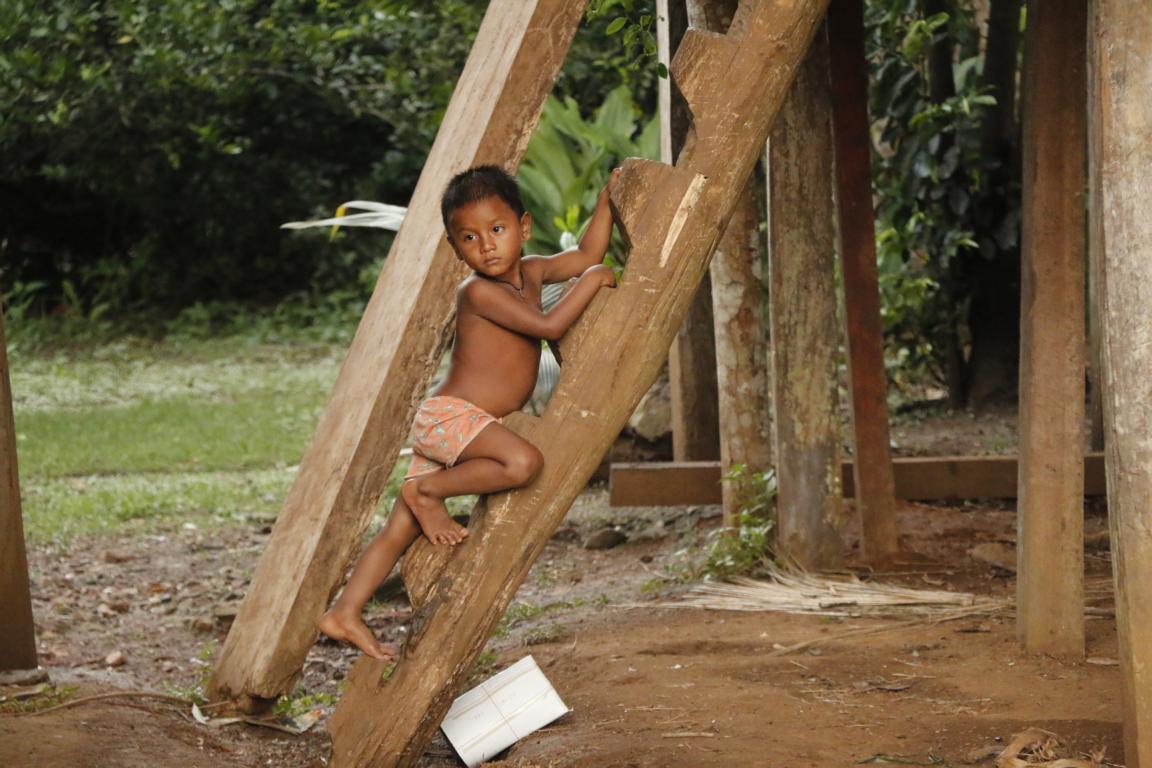

Children always like to pose.

From Puerto Indio it is a four-hour hike through the jungle to reach Villa Kerecia located on the Rio Tigre. Michel and I where quite soaked after the trek, just our guide Vidacho still was smiling.

The village is not connected to the electricity grid but since four months has running water transported by a pipeline from the mountains. Before that people were drinking the river water. While traditionally roofs are made out of palm leaves (which last about 10 years) some houses have iron roofs. These roofs are gifts provided by politicians to make people vote for them. While they are more durable the disadvantage of these roofs is that it is much hotter below. As it is only every other month that a foreigner comes to the village people asked a lot of questions about the “outside” world.

Pacho Manuel (82) told us of former times when he lived alone with his wife in the jungle and still was hunting with a blow pipe and bow & arrow. It was only in the 1980s when the government started building schools that people formed villages in order to enable their children to go to school. Embera language knows only numbers from one to eight. Everything beyond that is “a lot” (mucho).

A traditional Embera fire place for cooking. A basis made out of clay prevents that the floor catches fire.

All artisanry is made out of material coming from the jungle. Fibers are taken from leaves, washed, dried and encoloured using colors made out of local plants.

Ichi is producing jewelry by cutting and hammering Five-Cent pieces.

Michel always carries a well-equipped first aid kit and provides medical assistance where needed.

Preparing rice for consumption by unpeeling the rice.

A spontaneous cock-fight erupts.

Returning by piragua, the traditional boat built in one piece by cutting it out of a tree trunck. In case a person wants to build a new piragua the whole village is obliged to assist to cut the tree and to transport it to the next river. The shaping takes several weeks for two men working and a piragua has a life span of up to 20 years.