Guatemala North/East – July 2018

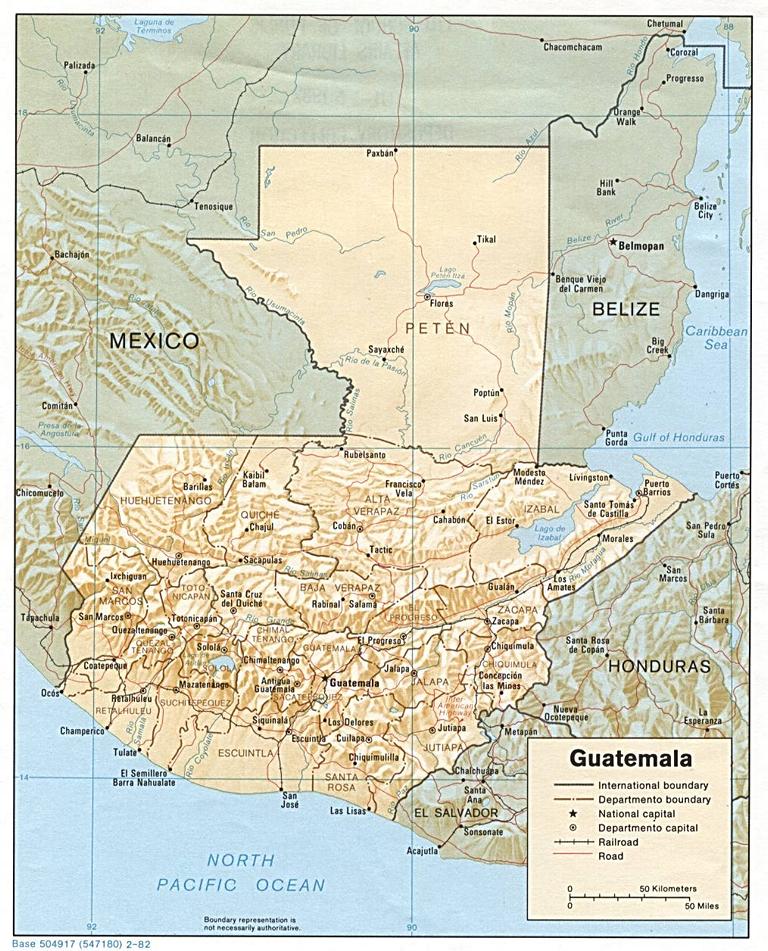

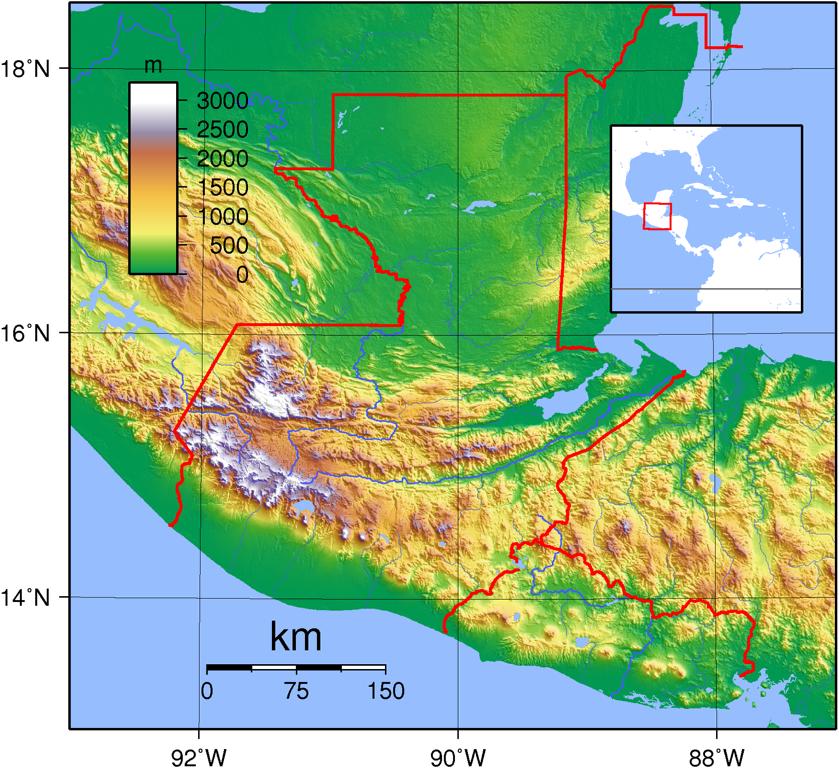

In July 2018 Ursula and I travelled through Eastern and Northern Guatemala. We started our tour in the Rio Dulce region in order to visit Guatemala’s Caribbean coast and then moved north to the Petén region to spend some days at the famous Maya archeological sites. Pictures in the following blog were taken be Ursula and me.

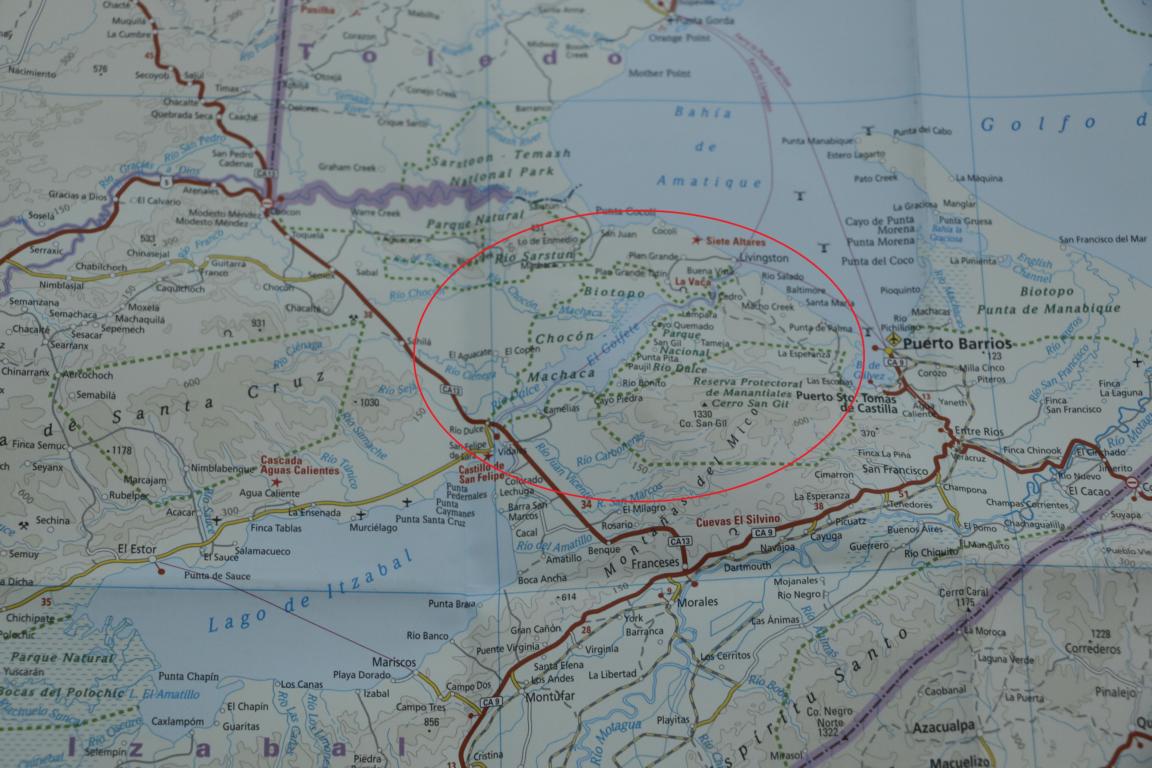

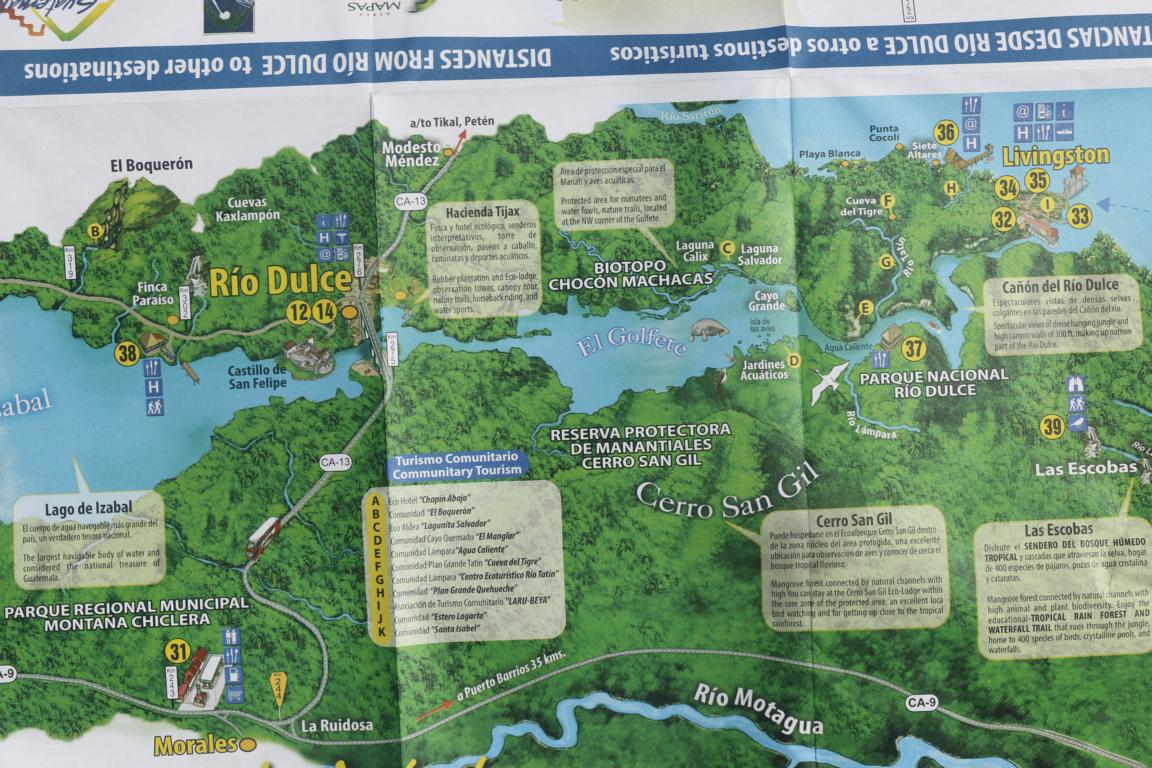

Squeezed between Honduras and Belize the Rio Dulce (Sweet River) which flows into the Bahia de Amatique for a long time was Guatemala’s main access to the Caribbean. In order to prevent British, Dutch and Portuguese pirates to move up the river the Spanish colonial administration from 1595 on built the small fortress San Filipe. Located at the eastern end of the Izabal Lake the fortress was the start of our 40 km boat trip down the Rio Dulce.

Street food in Rio Dulce is freshly made and very tasty.

The El Golfete Lake (2m above sea-level) is considered hurricane-safe and is popular with foreign boat owners who want to store their boat. Going down the river/lake we passed by mangroves and small settlements. Fishing is the main source of income.

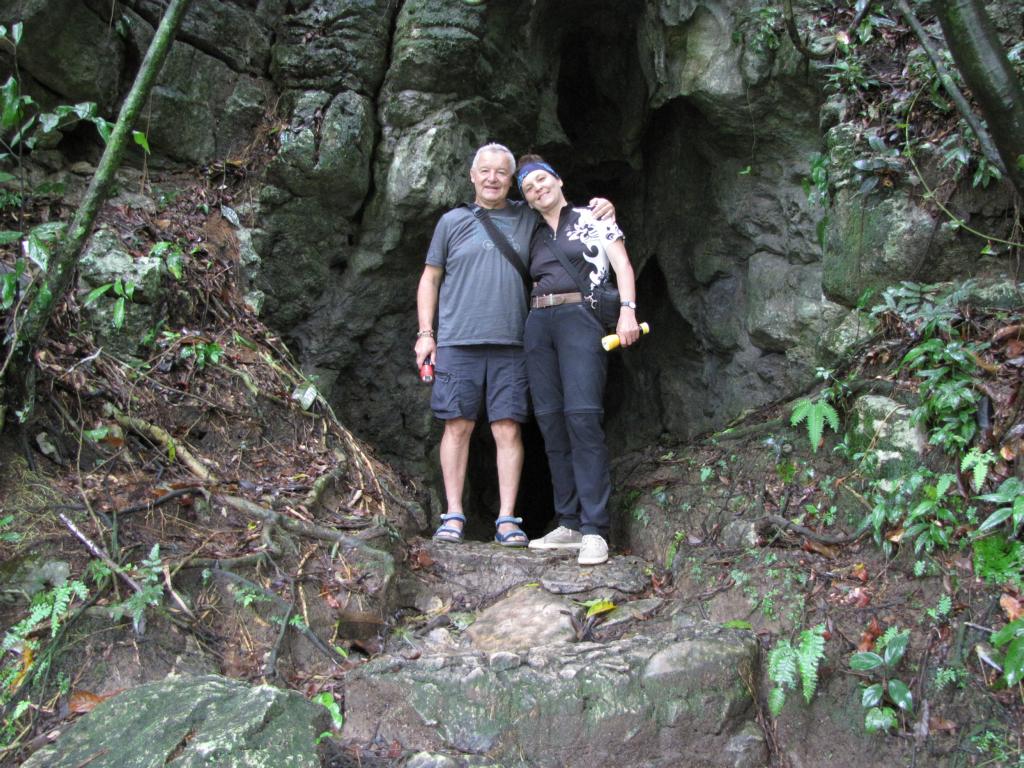

Aqua Caliente (Hot Water) is a popular stop as it not only offers thermal springs but also has three caves. In the first one it is possible to see some petrified animals. The third cave is something like a natural sauna as the hot springs are heating up the rocks. All caves are quite narrow, so you better do not suffer from claustrophobia.

Before the Rio Dulce reaches the open sea it flows through the Canón de Rio Dulce which cuts an impressive gorge through a several hundred meter high lime stone ridge covered by tense jungle.

Livingstone is an old harbor which can only be reached by boat. The town is famous for its mix of cultures: Garífuna, Afro-Caribbean, Maya and Ladino people. The Garifuna are decedents of African slaves who mixed with Caribs of the island of Saint Vincent (Lesser Antilles). Fearing slave rebellions, the British administration beginning of the 19th century forced some 2,500 “more-African-looking” men, women and children to mount some not-sea-worthy ships and left them to the mercy of the elements. After an odyssey the ships hit land at the Honduran coast where the former slaves started small settlements which spread to Nicaragua, Guatemala and Belize. Today the decedents amount to some 600,000 with large communities living in the USA. The Garifuna have their own language which combines elements of an Arawakan language with French, English, and Spanish influences. As fishing is less and less profitable many Garifuna rely on remittances sent by their communities in the USA.

Driving north to the Petén region we passed large cattle ranches. Horses still are important for agriculture and transport. Therefore, it is not surprising to pass by saddle-makers displaying their sophistically made products.

What is today divided between Southern-Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras some 4,000 years ago was the territory of the famous Maya civilization which started in 2,000 BC and is considered one of the six cradles of mankind.

The Maya civilization was a system of city states with a complex trade network. Many of the old cities and tensely populated regions were located in areas which are today overgrown by dense jungle. Mayas not only built impressive architecture but also developed a complex writing system and reached a high level in art, mathematics, calendar, and astronomy. Out of several thousand books written by the Mayas only four exemples still exist as the Catholic church and the colonial administration during the 16th -18th century destroyed Maya texts where ever they found them.

The decline of the Maya civilization started in 900 AC when many of the large cities (which had up to 120,000 inhabitants) were abandoned and the population moved north. While the reasons for the decline are not yet fully clear it possibly might have been a combination of causes, including endemic warfare, overpopulation resulting in severe environmental degradation, and drought (Wikipedia).

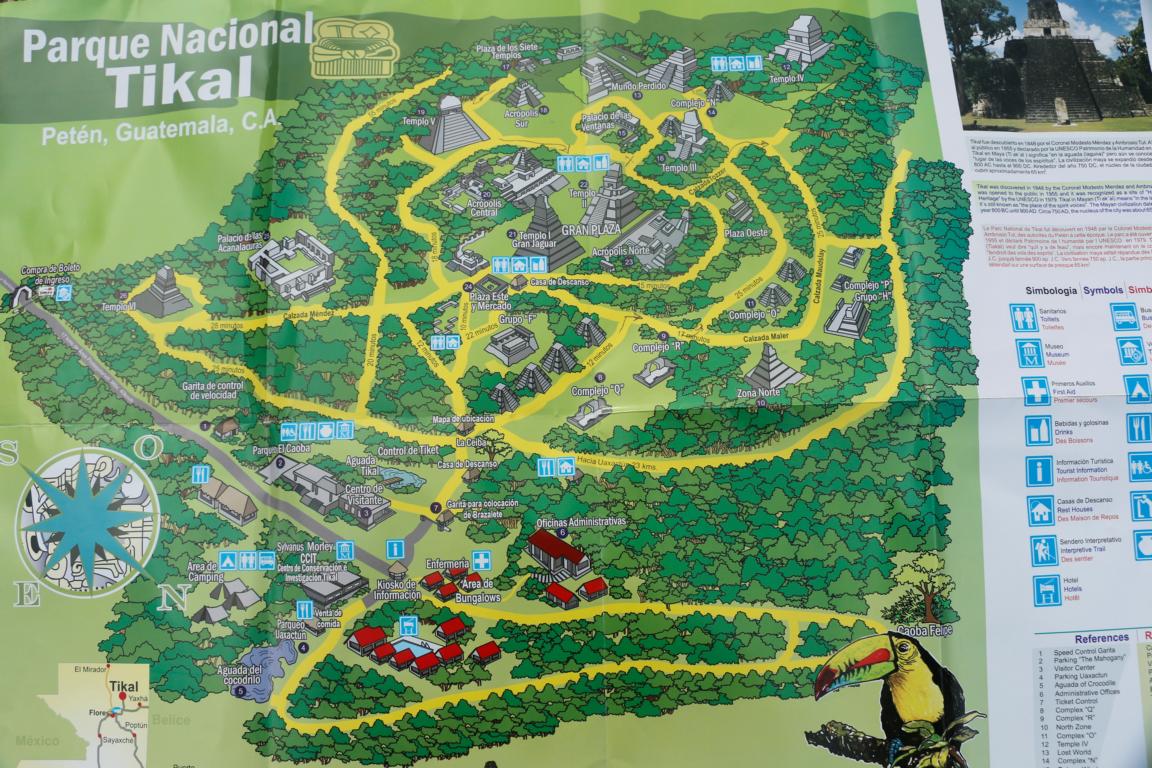

We first visited Tikal, located in the Tikal National Park, some 60 km north of Flores.

Tikal (rediscovered in the 1840s) during the period 200 - 900 AD was the most important Maya town in Guatemala. The town covered an area of some 16 sq km and was settled by up to 90,000 persons and another half a million people in the surrounding area. The town has been excavated in the 1960s and holds 3,000 stone structures. Photos taken from Pyramid IV (70m high) show other temples peeping out of the forest.

As the Maya did not know how to construct a dome bow or round arch the relatively small rooms all have a revers V-shape ceiling.

The “Acropolis”, the main square and two 47m high pyramids form the center of Tikal. Adjacent were government buildings, accommodations for the aristocracy and playing fields for the Maya ball game.

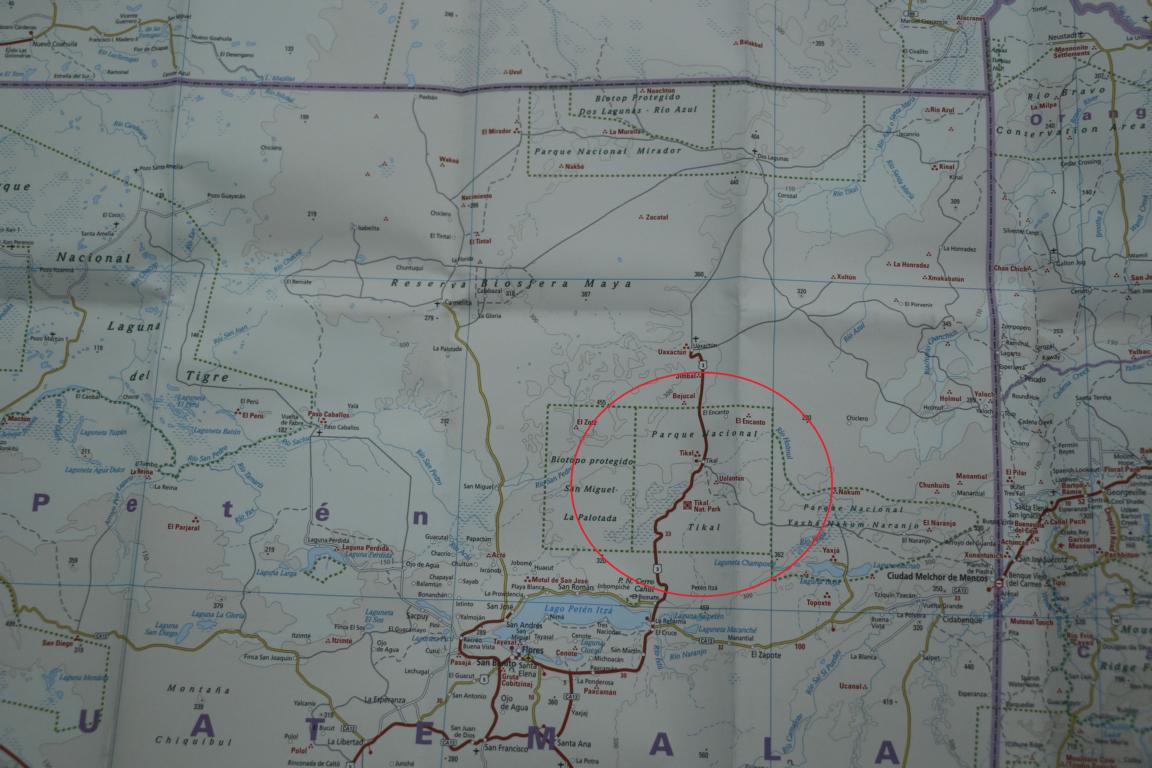

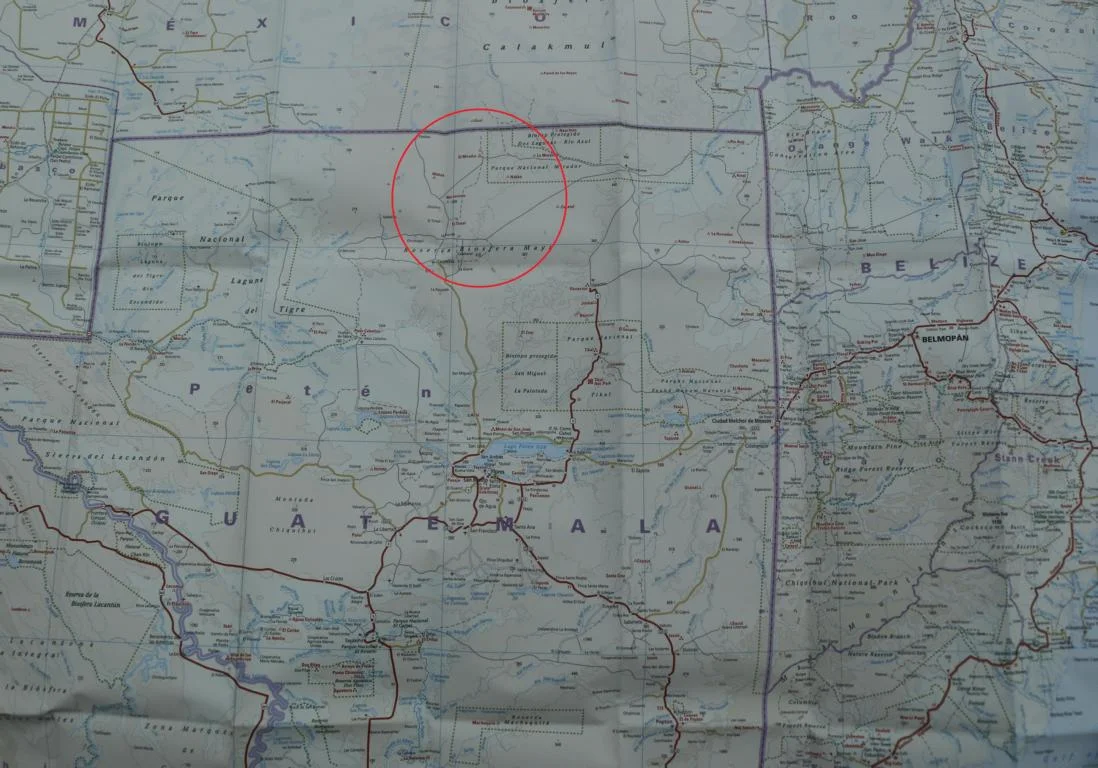

Friends in Guatemala gave us the advice to also visit an archeologic site called “El Mirador”, which is located deep in the jungle only four km south of the Mexican border. As the complex can only be reached via helicopter, a multiday walk or horse ride not more than 3,000 people visit the archeological site per year.

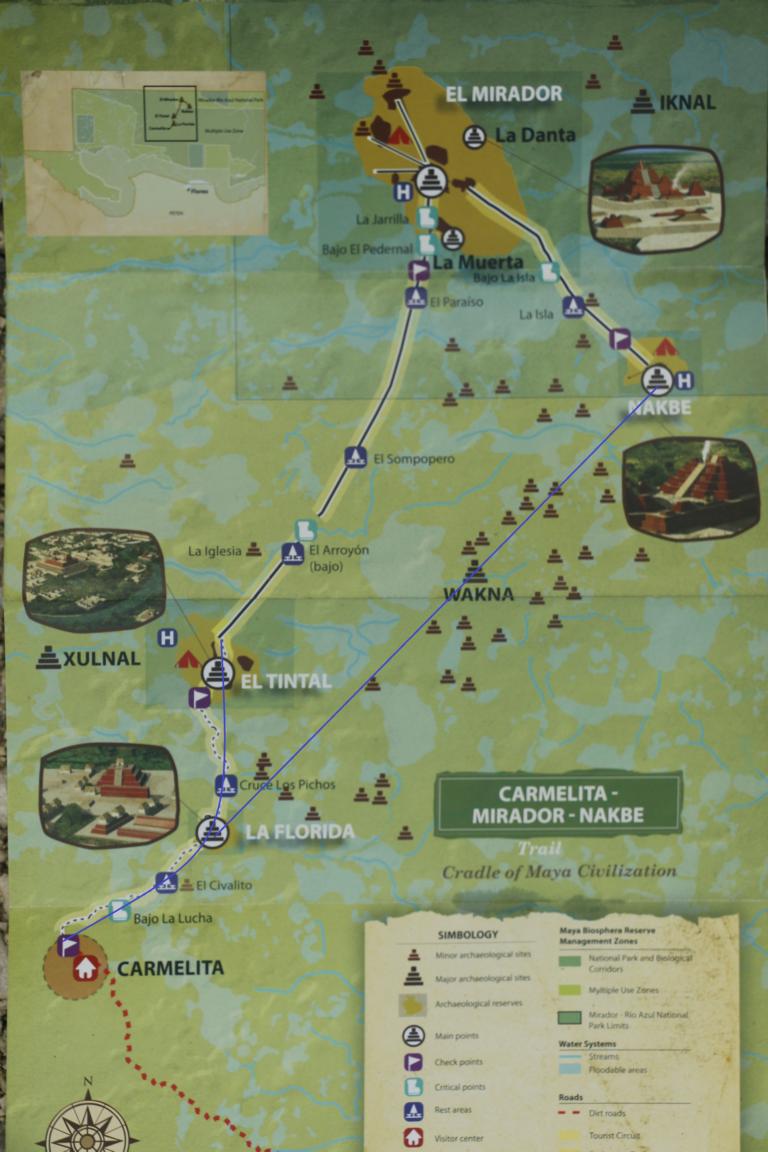

Ursula and I decided for a six-day circuit which would lead us to El Mirador and two other excavation sites: Nakbe and La Florida. We booked our tour through the Comision de Tourism Cooperativa Carmelita (https://turismocooperativacarmelita.com/) a local NGO where all the benefits stay with the local community. They provided us with a guide, a cook and a young man to drive the mules. Let me at this point take the opportunity to thank Angelica, Milton and Dalia for their excellent service. Ursula, who has younger legs than me, decided to walk the 100 km tour on foot, while I rented a mule for riding.

The tour started in the town Flores from where we took the “chicken bus” to Carmelita in order to meet our guides. Carmelita is a small settlement where the road ends. During the first days we were accompanied by Oliver, a German traveller.

The 40 km hike / ride to El Mirador took two days and followed an ancient Maya causeway which was part of a 240 km long network of roads – maybe the longest road system of the world at the time of construction.

On our way we passed a site where a new park ranger station is constructed.

The first Maya building which we visited was La Muerta (The Dead Woman) which probably was used as a funeral place. Archeologists found 46 sculls buried in the narrow tunnels. As you will see in the pictures unfortunately we were not alone in the tunnel, although the spiders were not as big as they appear in the photo.

During the night we slept in tents in jungle camps which provided some basic comfort and protection against the rain. The temperature fluctuated between 28 and 35 degree C (night/day).

For cooking Dalia and Angelica (who served as cook and guide) used the traditional Guatemalan oven consisting of a U-shape clay wall and a metal grill. Ursula used the opportunity to get her first lesson in how to prepare tortillas.

As there are no rivers in the whole Petén basin rain water is the only source of water. A method to collect it is to open a plastic sheet and to lead the rain water into a fabricated reservoir. For showering one uses a bucket, the toilet is a pit toilet.

As it gets dark at 19.00 hours evenings can get quite long. Anyway, we went to bed early as usually we had to get up at 4.30 the next morning.

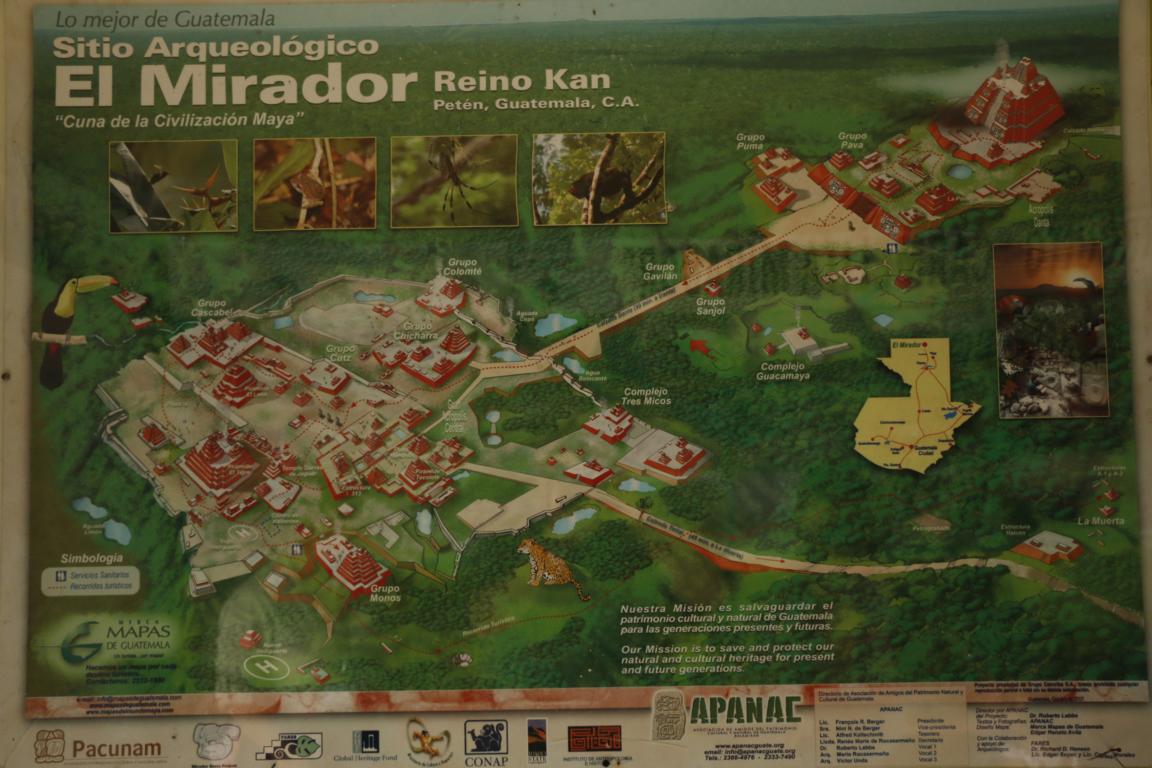

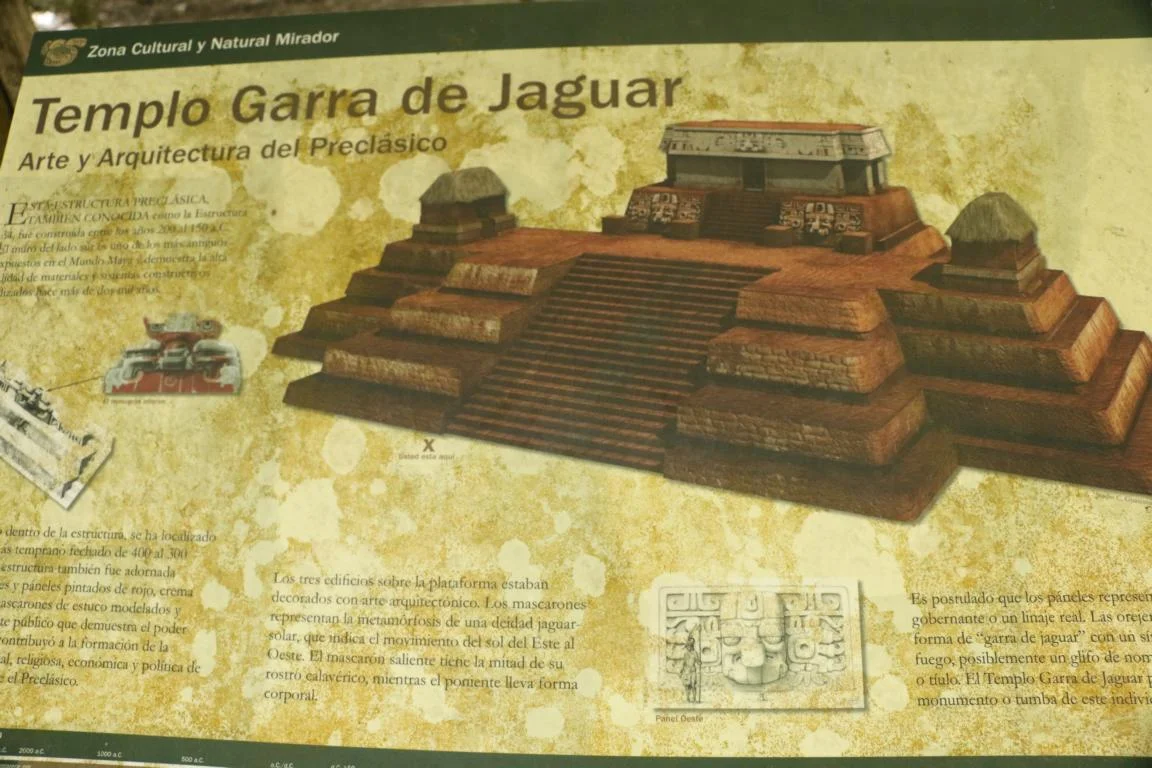

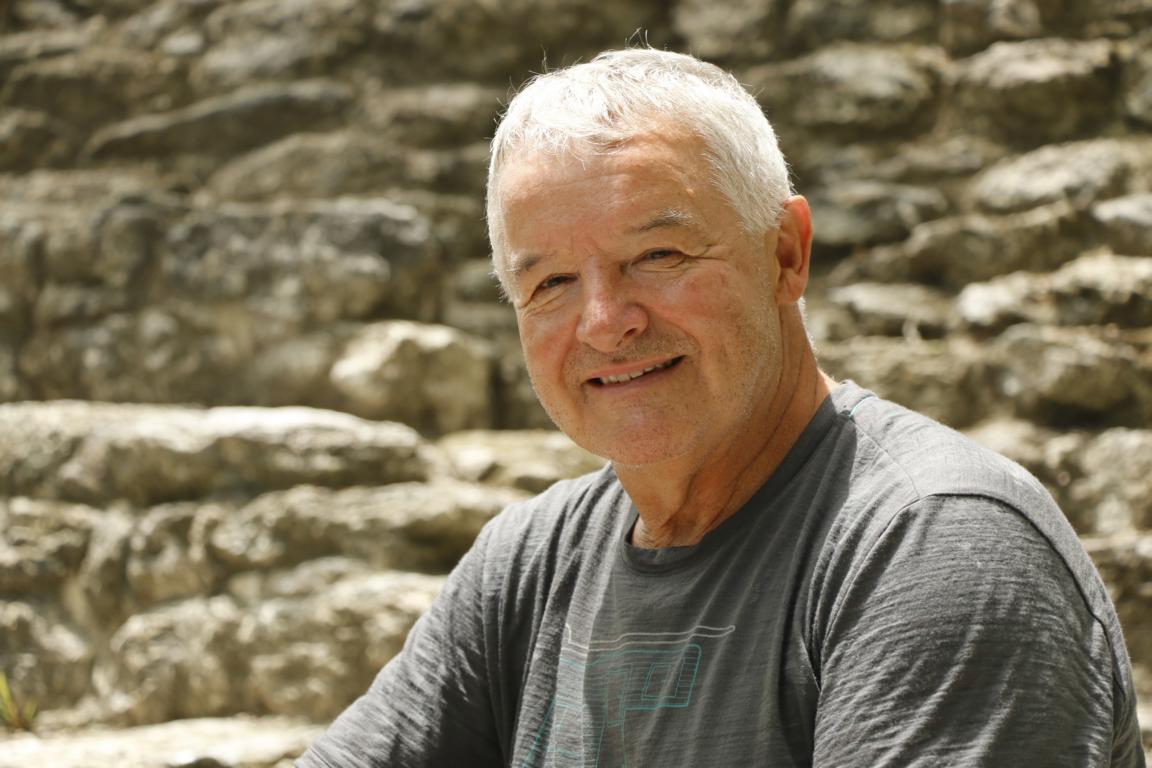

On the third day we finally visited El Mirador which has been re-discovered in 1926 and is currently excavated by a team led by Richard Hansen (see him in the third picture) from the Idaho State University. During its glory days (600 BC until 300 AD) the city of El Mirador extended over 26 sq km and was the most important Maya city. Excavation are currently going on in the Paws of the Jaguar Temple and the Acropolis, where a large frieze has been detected reciting the mythological story of two ball game players who played and fought against the gods of the underworld. Photos may provide an impression how overgrown the site was before the excavation and restauration started.

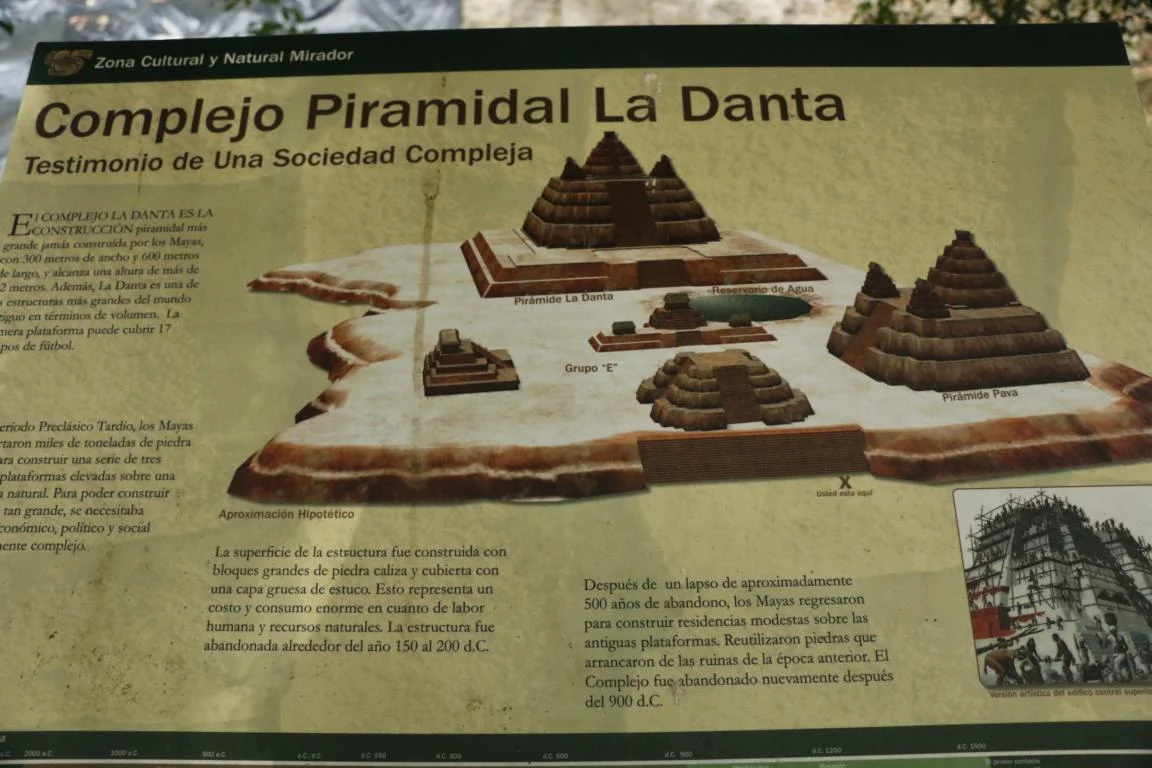

El Mirador is not the original Maya name of the city. The name (translated as lookout, view point) stems from its two pyramids El Tigre (55m high) and La Danta (72 m high), which raise above the jungle and provide a fantastic view. La Danta, built on three platforms of which the lowest has the size of 17 football fields, is among the biggest pyramids of the world with a total volume of 2,800,000 cubic meters.

The construction of the prestigious monuments contributed to the deforestation and soil erosion of the surrounding territory. Mayas not only used cement to put the stones together but also covered buildings with plaster and stucco. Archeologists have calculated that for the production of 1 ton of lime cement, 5 tons of limestone and 5 tons of wood were needed (Wikipedia).

While there were plenty of insect mosquitos were not really a problem. The first photo shows a firefly (with its “lights” turned off). It is quite common that tarantulas crawl through the camp at night.

From El Mirador it was a 14 km walk to the next site. Nakbé was established from 1400 BC on as one of the earliest Maya towns. Due to lack of building material it later was overtaken by El Mirador. In Nakbé we were able to visit an ancient quarry were the limestone was broken. As metal was unknown Mayas used stone axes made out of chert (a very hard stone) with a wooden handle glued together with the gum of the rubber tree to cut and shape the limestone blocks.

The fifth day was the toughest. We had to walk / ride 34 km from Nakbé to La Florida. Unlike the previous days this part of the trail is seldomly used and partly overgrown. Considering the difficult road conditions, we are quite content, that we made it in 9 hours.

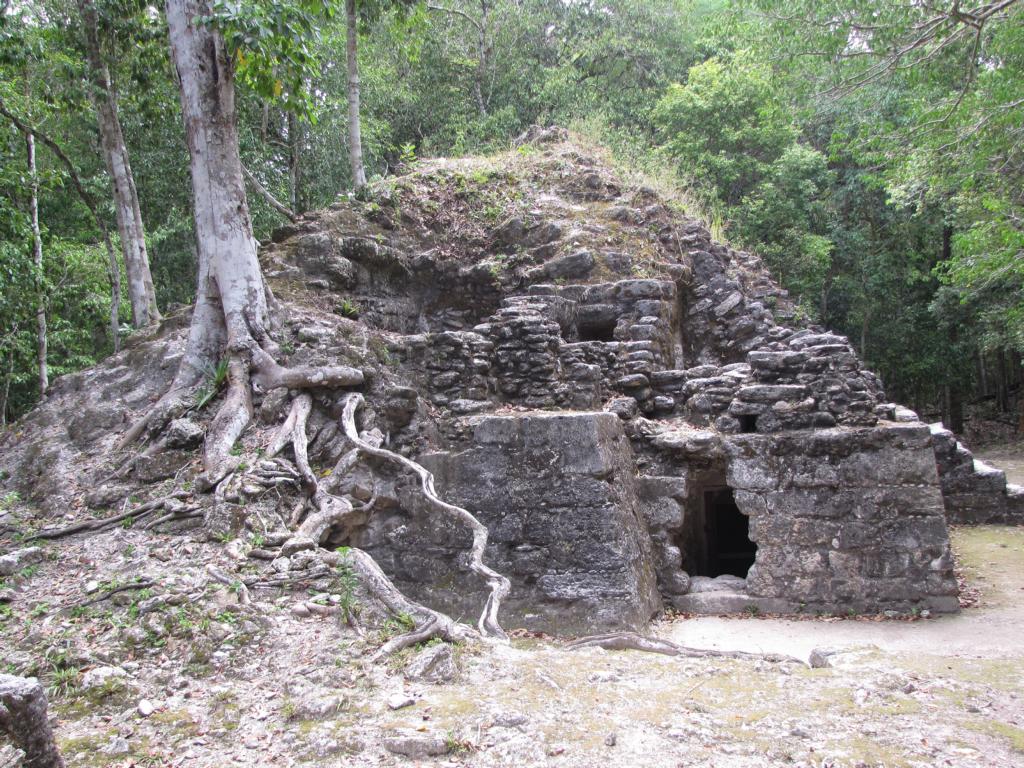

La Florida was a small Maya settlement which is partly excavated. Its economic importance originated from a chert mine which provided stones used to produce tools and weapons.

All Maya heritage sites in the jungle are under constant threat of looters (saceros) who break up the sites in search of artefacts which are sold on the black market. Not only are many precious pieces lost but the site itself also is destroyed and often cannot be reconstructed. Allegedly there are thousands of holes originating from looters similar to those shown in the following pictures.

As there is no grass in the forest Milton our horse driver had to feed the mules with the leaves and branches of a special tree. In order to get to these branches, he had to climb every day on one of the trees and to cut the branches with his machete. For climbing he used spikes which he tied to his legs.

Finally, I want to thank “Pepe” the mule who carried me six days through the forest. He was very patient and sure-footed. It certainly was not his fault that the saddle was a bit painful for my but.

Eventually a few photos showing that we survived in good health and the spirit is still high.