El Salvador 1980 and 1981

In 1980/1 I worked four months as a journalist in El Salvador for Austrian newspapers, which was quite dangerous at that time. Some months after my departure four Dutch journalists were ambushed and killed by the army. Looking back my collegues and I every day took quite a high risk.

Writing for a newspaper was quite different from what it is today: Prior to fax machines journalists sent their articles via telex, which means one had to write the text by punching wholes into a paper-tape which then was fed into a machine transmitting the message. Furthermore I used two cameras, one for black & white photos (which were cheaper) and another one for color slides. The black & white films and photos I was able to develop myself in an improvised dark chamber in the hotel bathroom. However, I had to cool down the temperature of the cemicals with ice cubes as the tap water was to warm for developing the film (a temperature between 18 and 22 degree C was required). Sending the photos to the newspaper was another headache: I had to rely on airline passengers flying to Europe asking them to post the envelope at the nearest post office in Europe. Photos shown in the following blog were later digitalized.

Historic Background:

After indigenous communal land had been abolished and confiscated fourteen families since the 19th century owned up to 90 % of the land in El Salvador. In 1932 a rebellion of campesinos (farmers) led by the newly formed Communist Party under Farabundo Marti tried to establish a more even distribution of property. The rebellion was crushed by dictator Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. During the so-called "Matanza" (massacre) some 30,000 members of indigenous tribes were killed. The use of native language and tradition was banned ending the existence of indigenous people in El Salvador.

Against the background of continued social injustice, fraudulent elections in the 1970s and the successful revolution in Nicaragua in 1979 resistance again built up in El Salvador. By the end of the 1970s death squads (escuadrones de la muerte) started targeting left-wing oposition and catholic activists killing 10 to 30 persons a day in the capital San Salvador. The most prominent victim was Archbishop Oscar Romero, an outspoken critic of the government, who called for far-reaching social reforms and appealed to soldiers to disobey orders when they are told to shoot people. He was himself assassinated by a right-wing death squad on 24 March 1980 while conducting a mass ceremony.

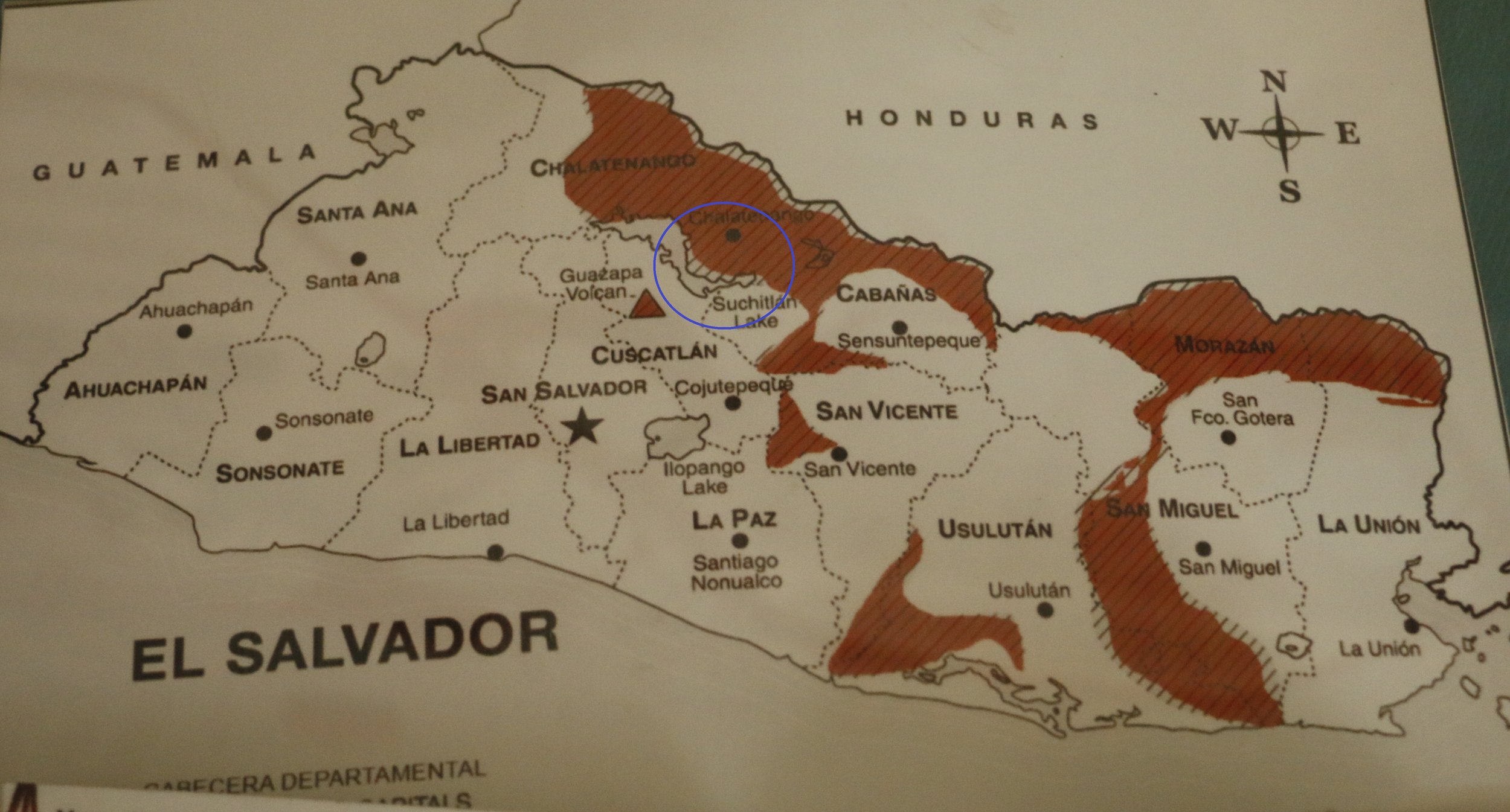

Frustrated and disillusioned by the inability to change the power balance through non-violent means a rising number of activists joined armed groups which in October 1980 united in the guerilla movement Frente Farabundo Martí de Liberación Nacional (FMLN). During the Salvadorian civil war, which lasted from 1980 until 1992 and cost 70,000 lives. While I was in El Salvador during the starting period of the FMLN the guerrilla later professionalized and obtained better equipment. During its offensive in 1989 the FMLN temporarily was able to bring 2/3 of the country under its control. The government army received massive training and equippment by the USA. The FMLN relied on support from Cuba, Nicaragua and Mexico.

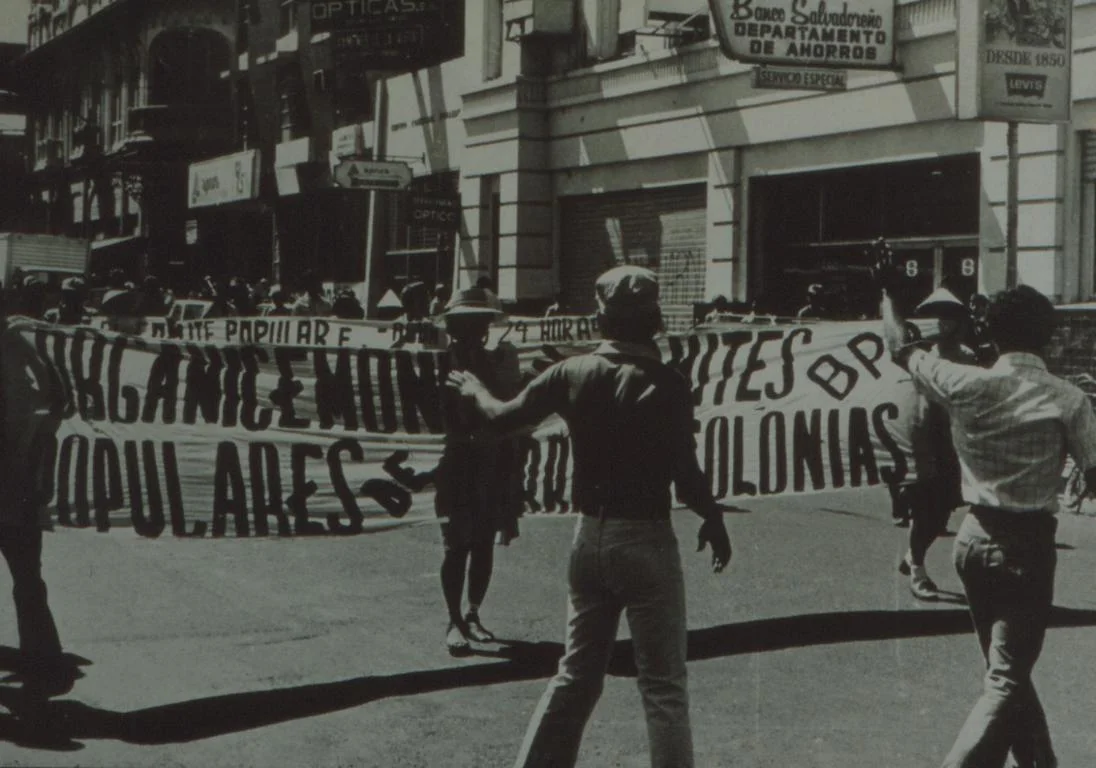

The following five pictures (taken by other journalists) show the mounting resistance in El Salvador in 1980: Meeting of several guerilla movements at the university in San Salvador; strikes and demonstrations; Archbishop Romero, who was assassinated on 24 March 1980 by a right-wing killer commando.

My first work on El Salvador was related to the massacre at the Rio Sumpul, a border river between El Salvador and Honduras. On 14 May 1980 more than 300 Salvadorian refugees tried to flee to Honduras crossing the river Sumpul. Honduran soldiers forced the refugees to turn back and on the Salvadorian side of the river Salvadorian soldiers killed more than 300 men, women and children. Information about the massacre soon spread in the capitals but was strongly denied by the governments of both countries involved.

The only way to verify was to go there. I joint forces with a Chilean journalist Gabriel Sanhueza and a female German journalist (unfortunately cannot find her name anymore). As the massacre had occurred in a very remote region it took us three days starting from the capital Tegucigalpa to reach the place. In order to prevent journalists to conduct investigations the Honduran army had sealed off the area. When we reached an army outpost with three bored conscripts we simply played football with the young soldiers and after one hour left the village on the other side. Some five km before the border we found a wounded woman with a baby (see below) who was hiding in a farm house. She told us the story how she unsuccessfully tried together with the other refugees to reach Honduras and then survived the subsequent massacre by Salvadorian troops by hiding in the bushes after being wounded.

A local farmer later brought us to the location where the refugees had tried to cross the river. The photo shows the Rio Sumpul which at that time was about 50 m wide and 60 cm deep. We decided that it would not be wise if we all three cross the river as we did not know whether or not there were soldiers on the other side. As my colleagues had children I had a strong argument that it should be me to wade the river and to take pictures (in fact: It would have been more difficult for me not go than to go).

On the other side of the river the banks and medows were littered with bones, rips, skeletons, sculls, shoes and pieces of cloth. The massacre had taken place six weeks before we came to the scene and in the meantime animals had eaten most of the human flesh. I was not able to count the bodies as the were scattered over a wide area but they were many.

Apart of the human tragity crossing the Rio Sumpul was one of the most intense experiences in my life and in many aspects was a turning point for me. Not knowing whether there were soldiers on the other side who certainly would have killed me immediately I was every second during the crossing of the river expecting the impact of the bullets. As projectiles are faster than sound I did not listen with my ears but with my skin. After having taken the pictures, wading back through the river and reaching the safe river bank I was full of adrenalin and like on drugs. Crossing the river meant – as I later realized - that I had overcome all my fears: From that moment on I was never afraid anymore of dangerous situations, risks, supervisors, officials, …. And I also realized something else: Having survived was such a wonderful feeling that I wanted to experience it again and again in the following weeks by taking more and more risks (one in fact can get addicted to adrenaline).

During our return to Teguzigalpa the German female journalist smuggled the film roles in her underpants through the military checkpoints.

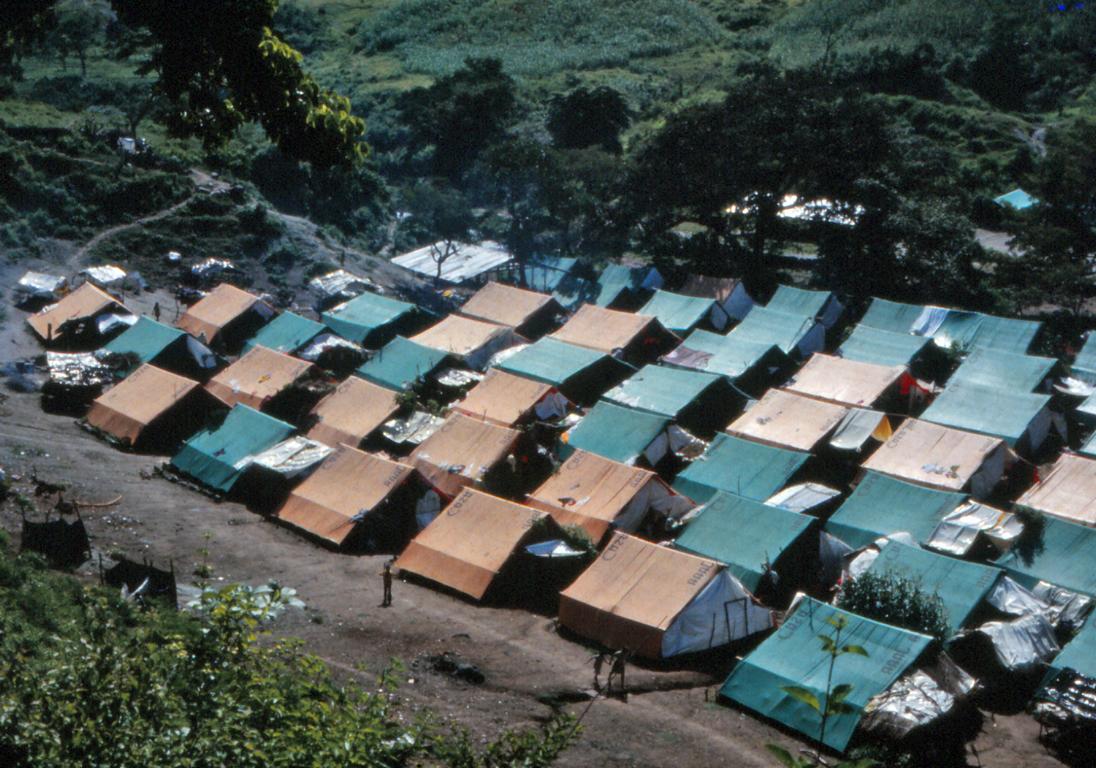

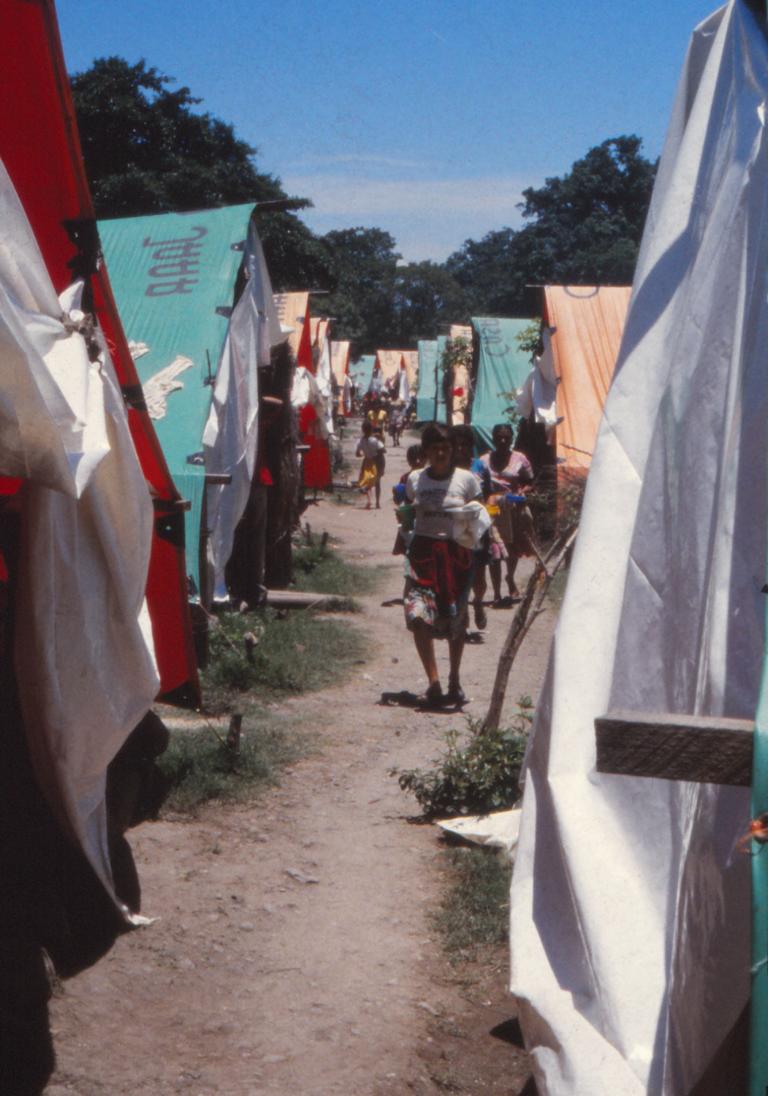

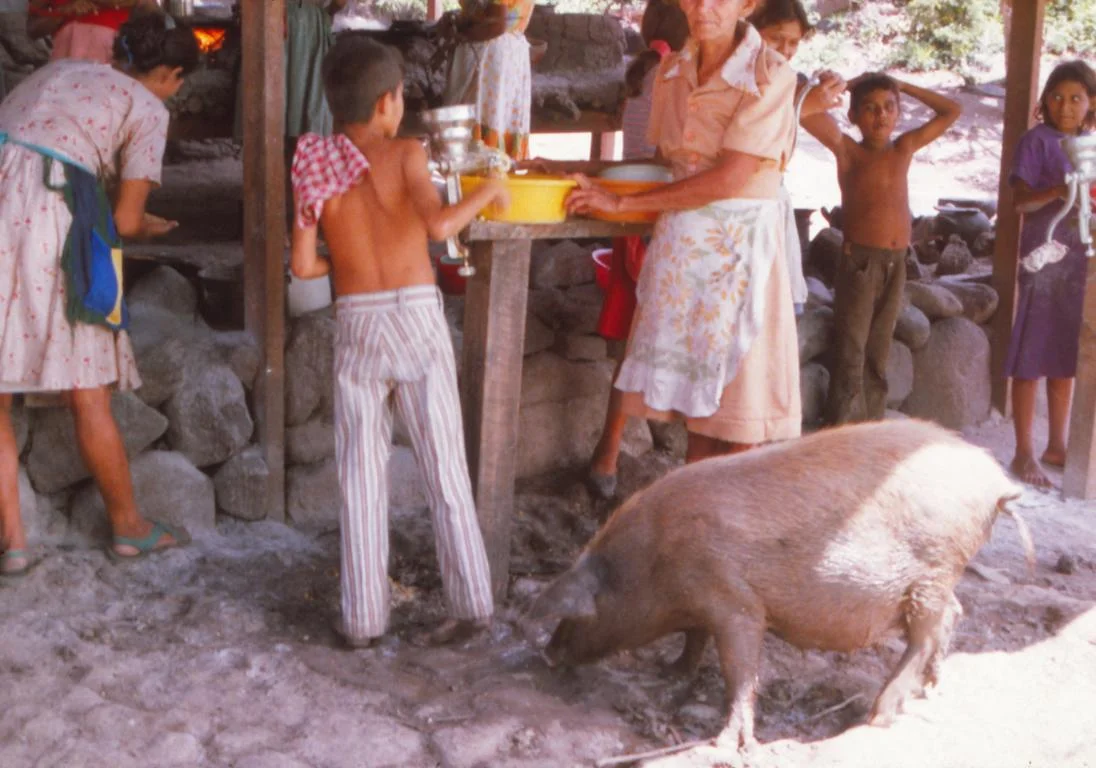

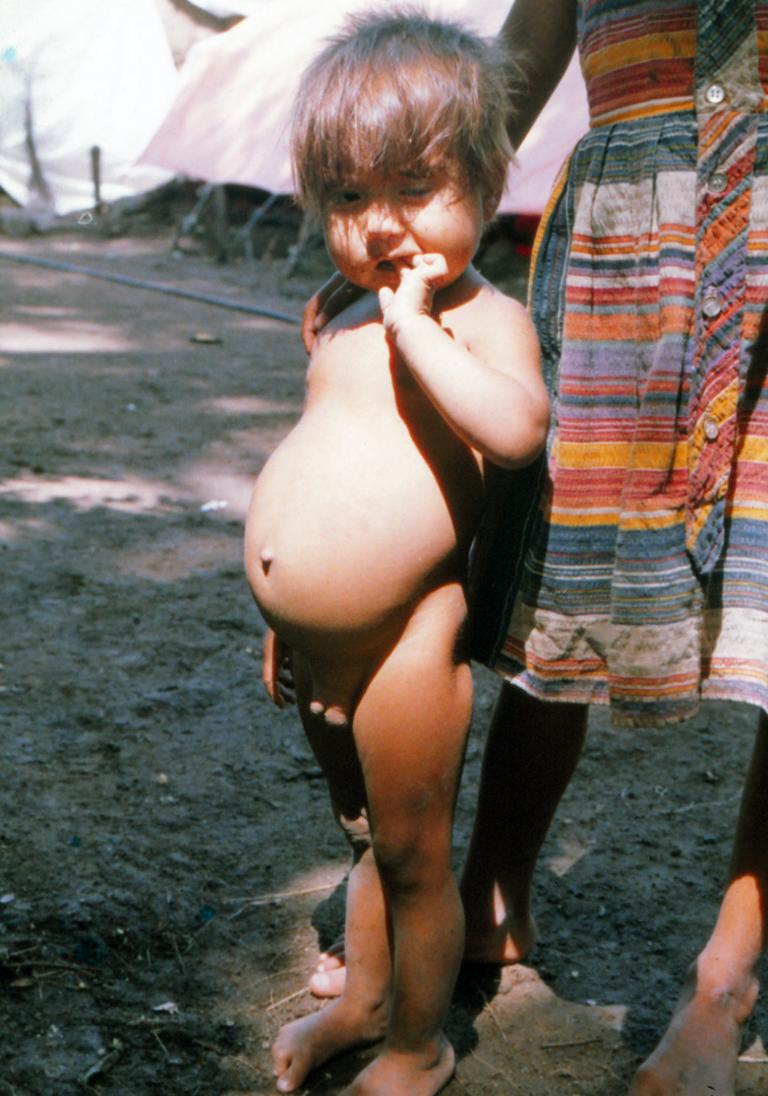

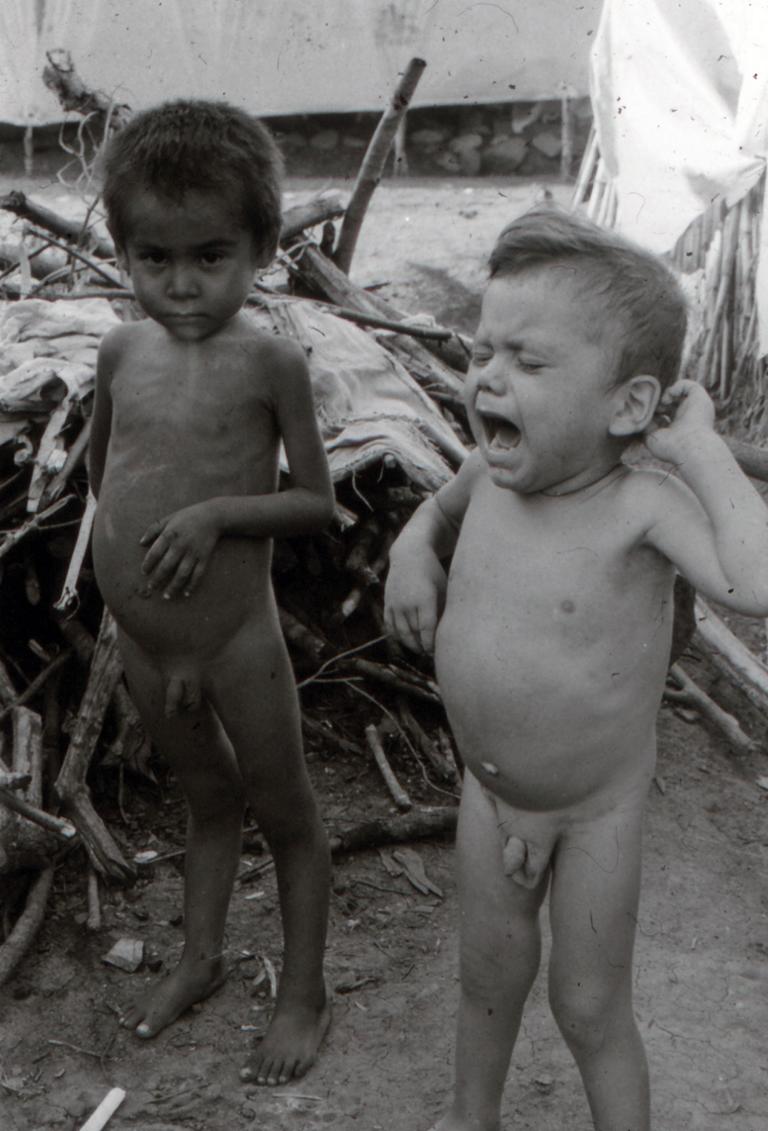

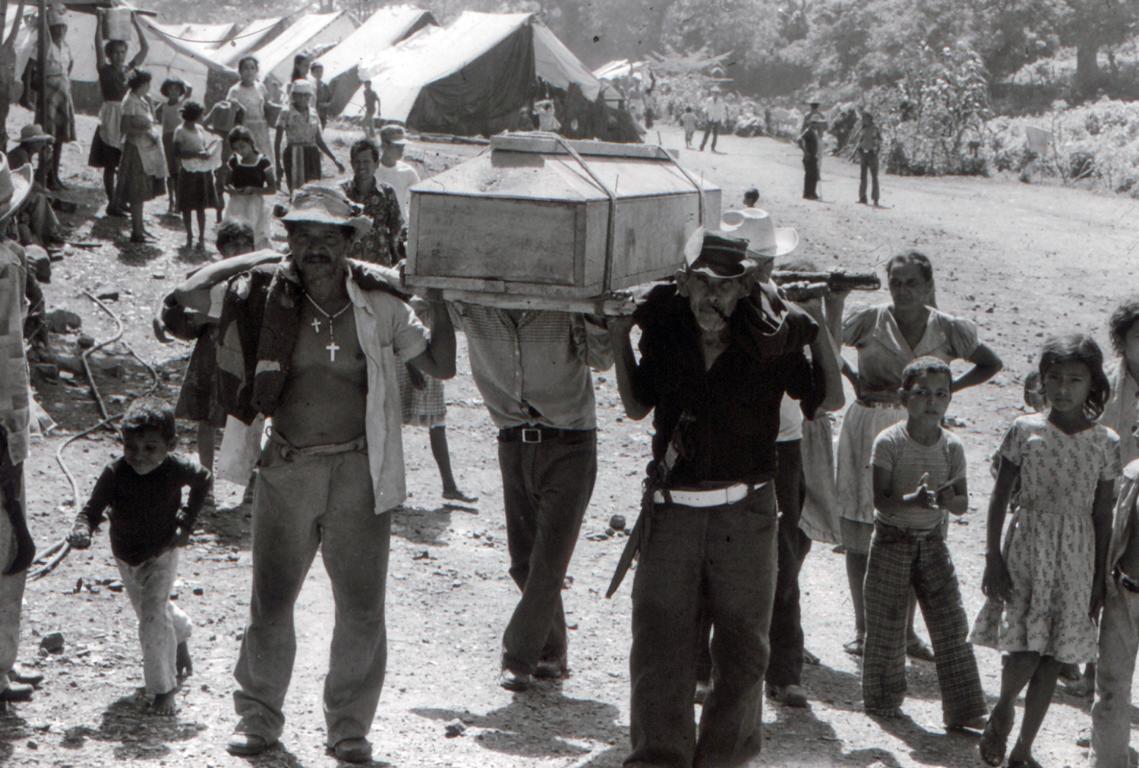

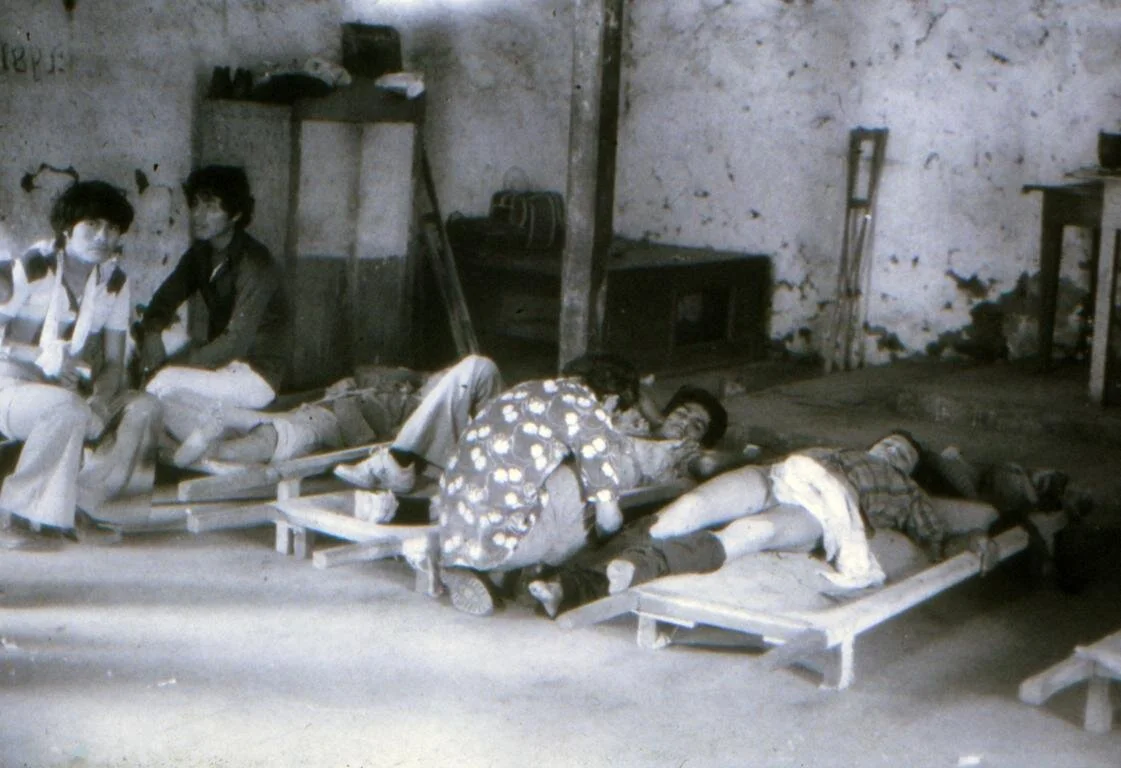

In summer 1981 I visited a refugee camp in Colomoncagua in Honduras. The Red Cross which maintained the camp flew a group of journalists to this camp which was located close to the Salvadorian border. The camp had been established to protect thousands of refugees who had fled El Salvador since summer 1980. Photos show everyday life in the camps.

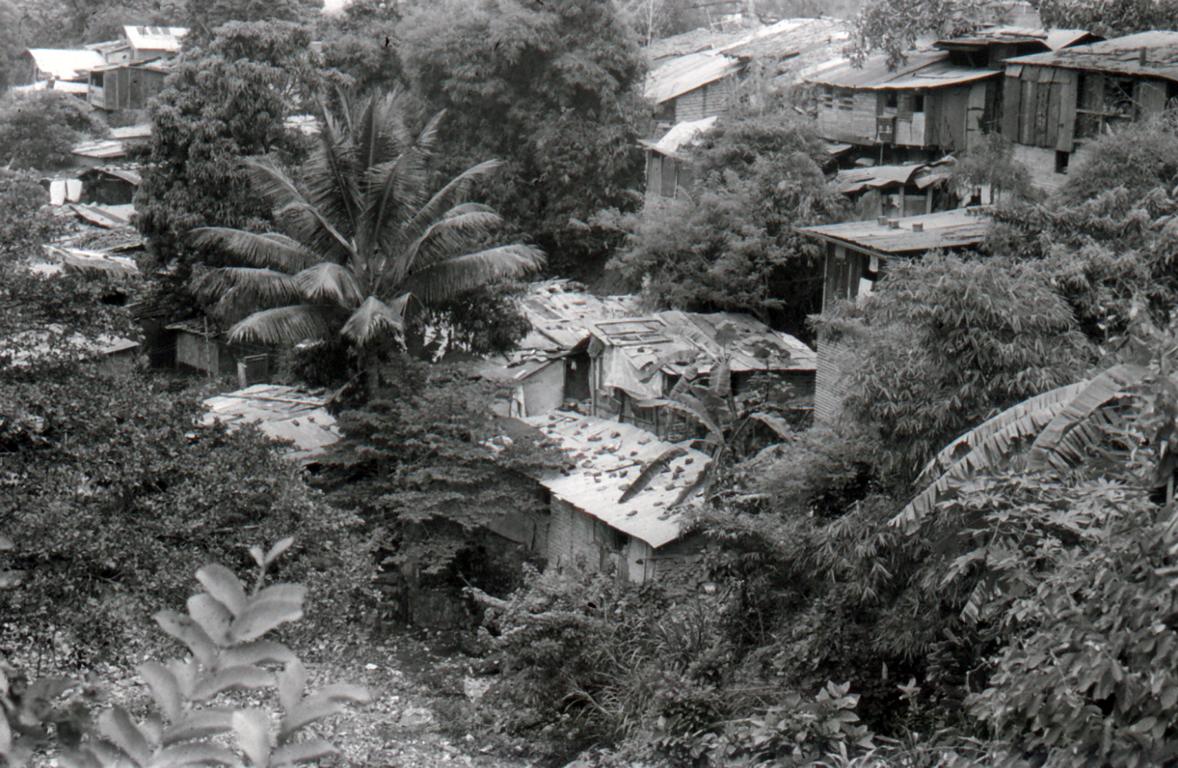

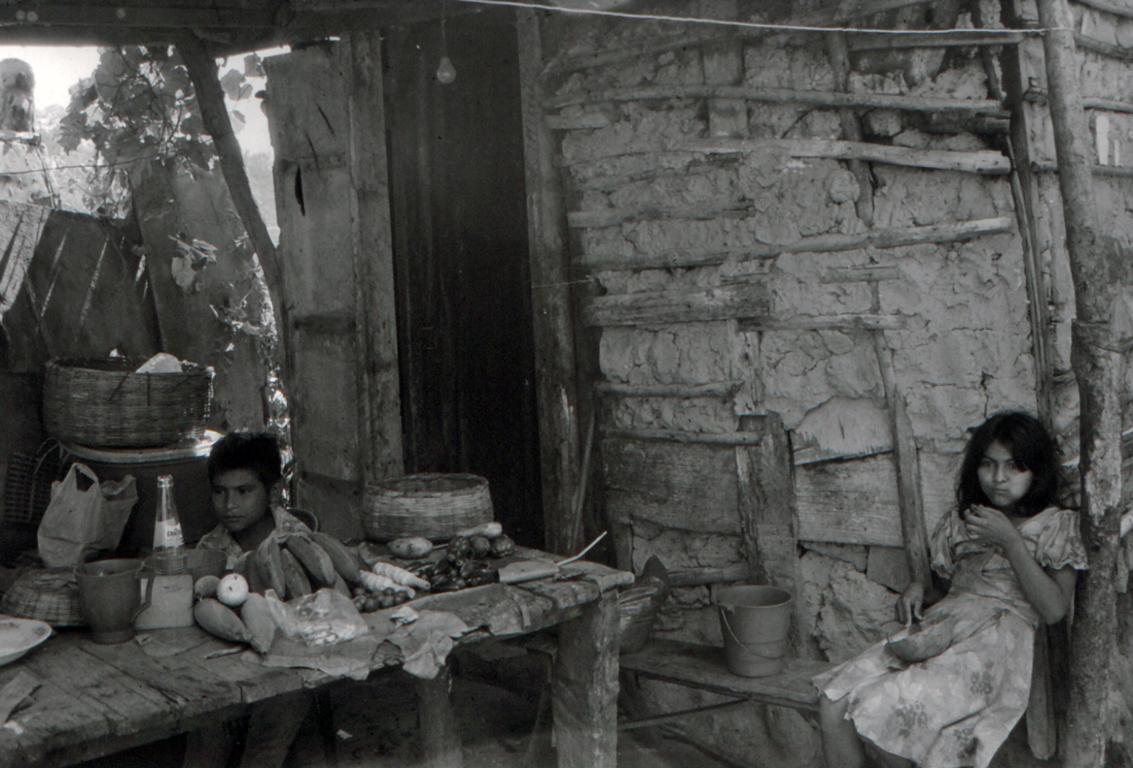

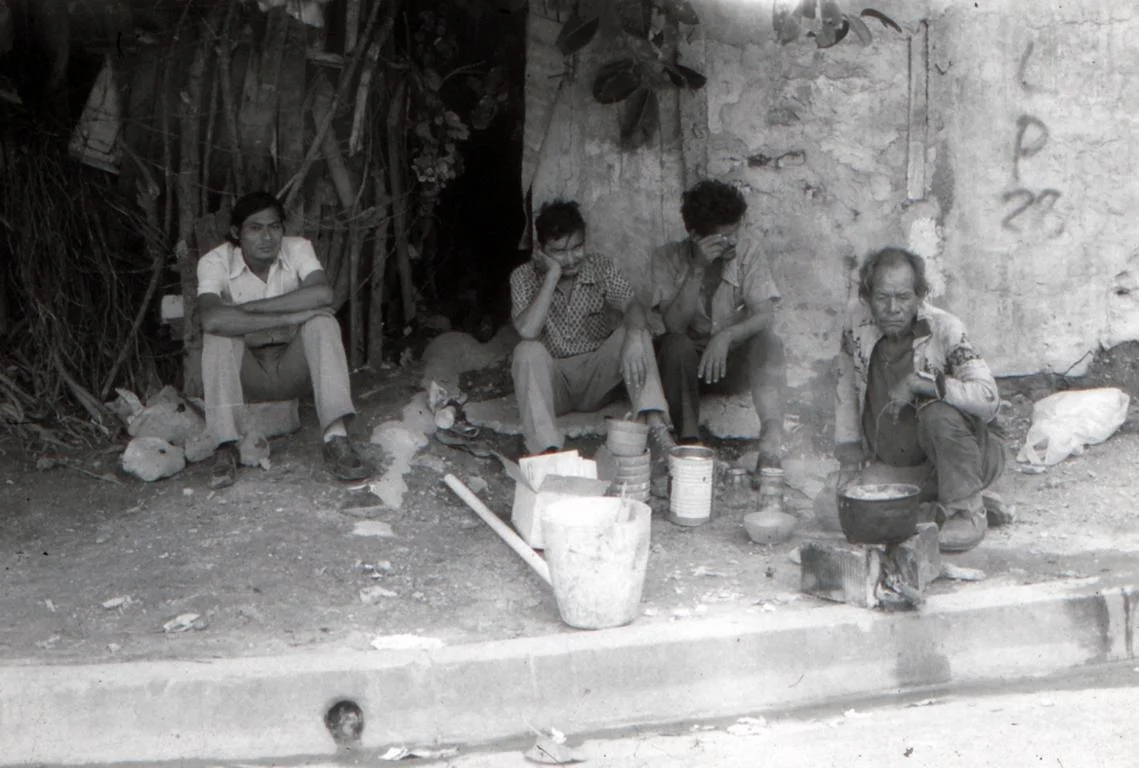

Around San Salvador’s urban city center there was a ring of poor neighborhoods where people lived in absolute misery.

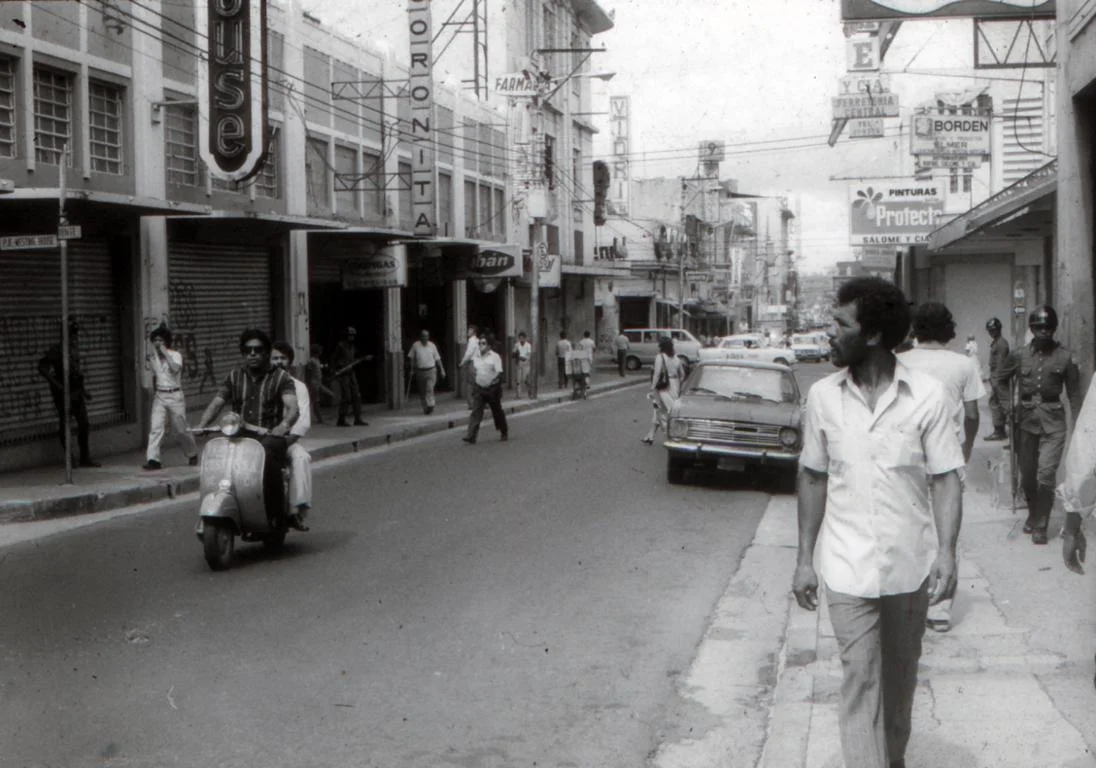

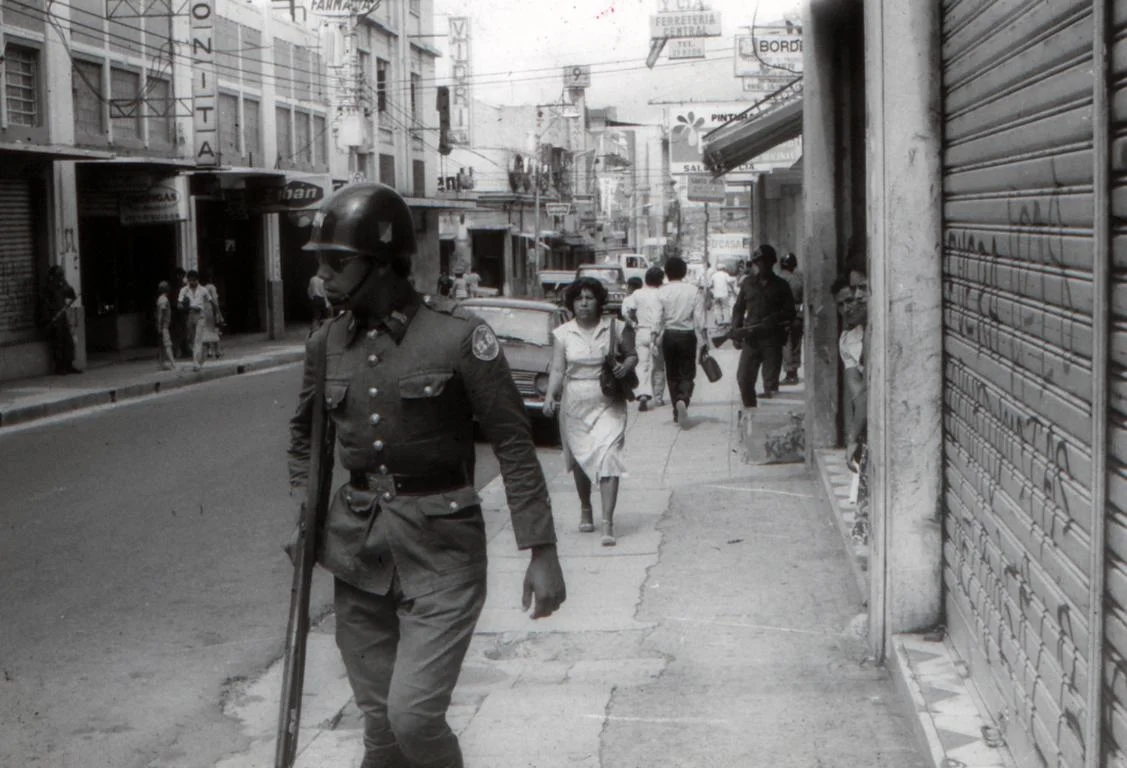

San Salvador in 1980/1 was a highly militarized city with patrols of the notorious policia nacional and the guardia nacional present everywhere. Both units where later dissolved as part of the peace agreement. Beyond that there were private pro-government militia and civilian defense groups operating, e.g escorting busses or securing buildings.

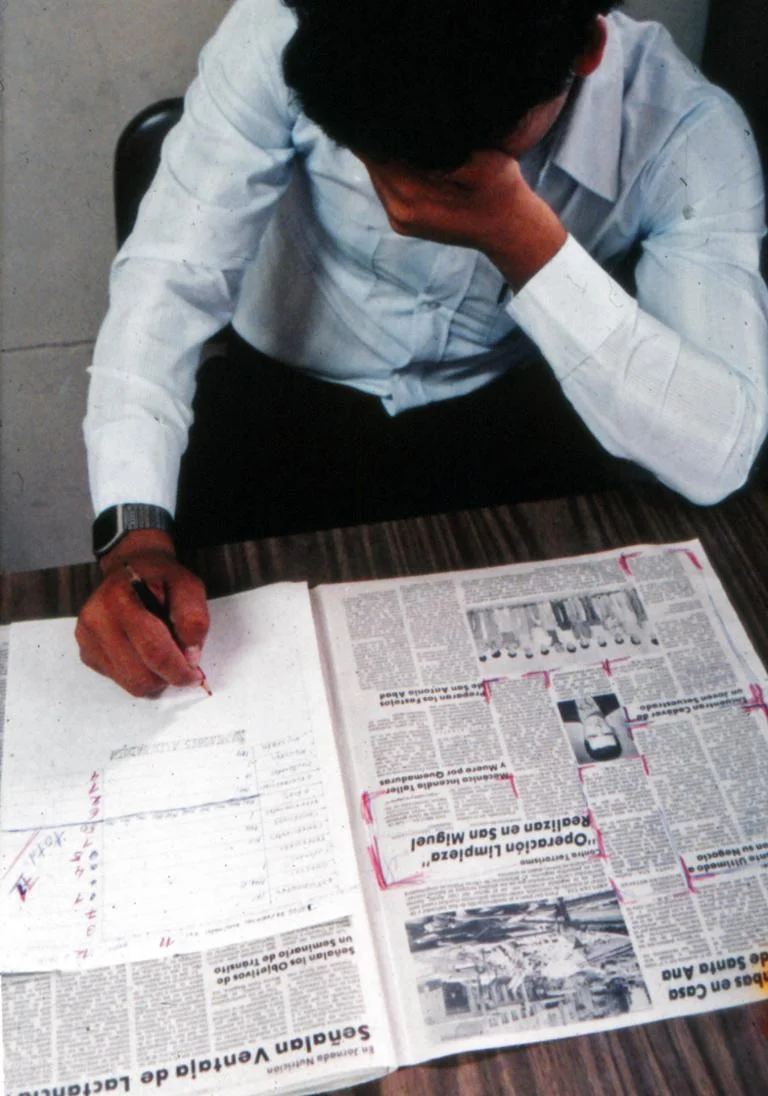

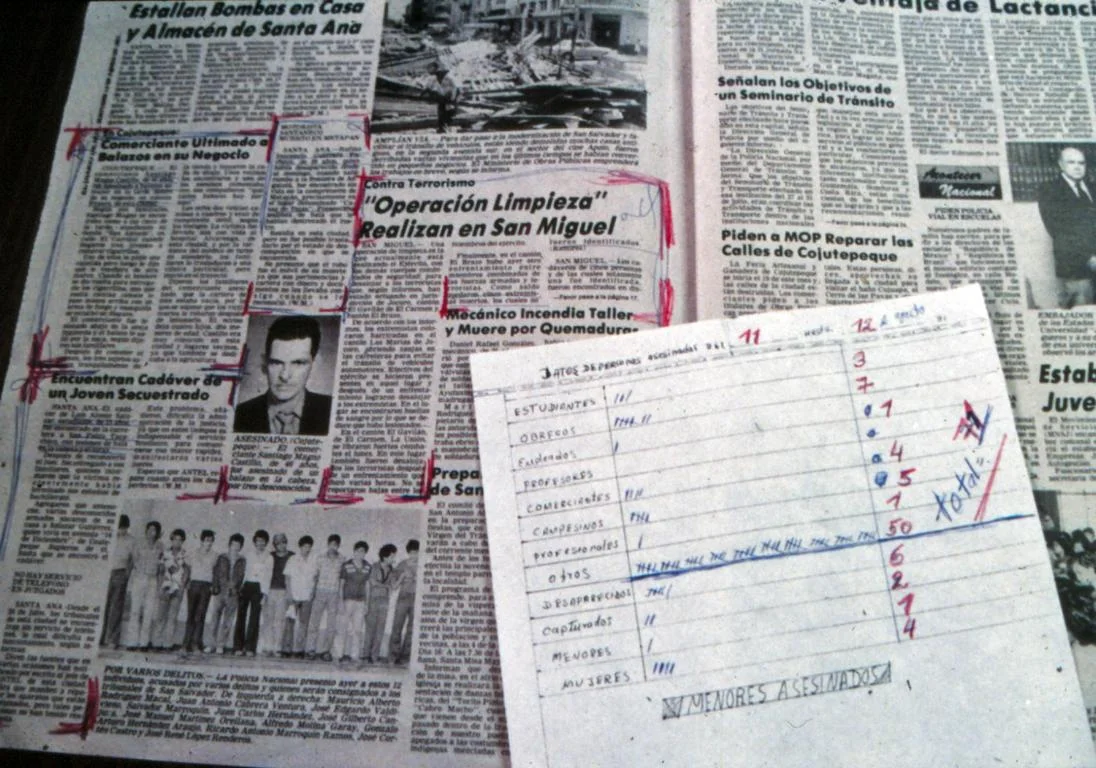

In 1980/1 the most horrible atrocities were the ongoing killings of students, civilian leaders, trade unionists and catholic activists by right-wing death squads. I frequently visited the offices of several human rights organizations which established records of the civilian victims of the death squads. Information was received from witnesses, relatives of victims or simply taken from the newspaper. The list on the photo contains 71 persons assassinated during the period 11 till 12 August 1981. The offices also shared their photo achieve with me.

As part of my work I drove every day in the morning a certain route visiting places where the death squads dumped the bodies of their victims. Below photos show two of the many victims I have seen during that time. Many of them were dragged out of their houses and then killed on the street.

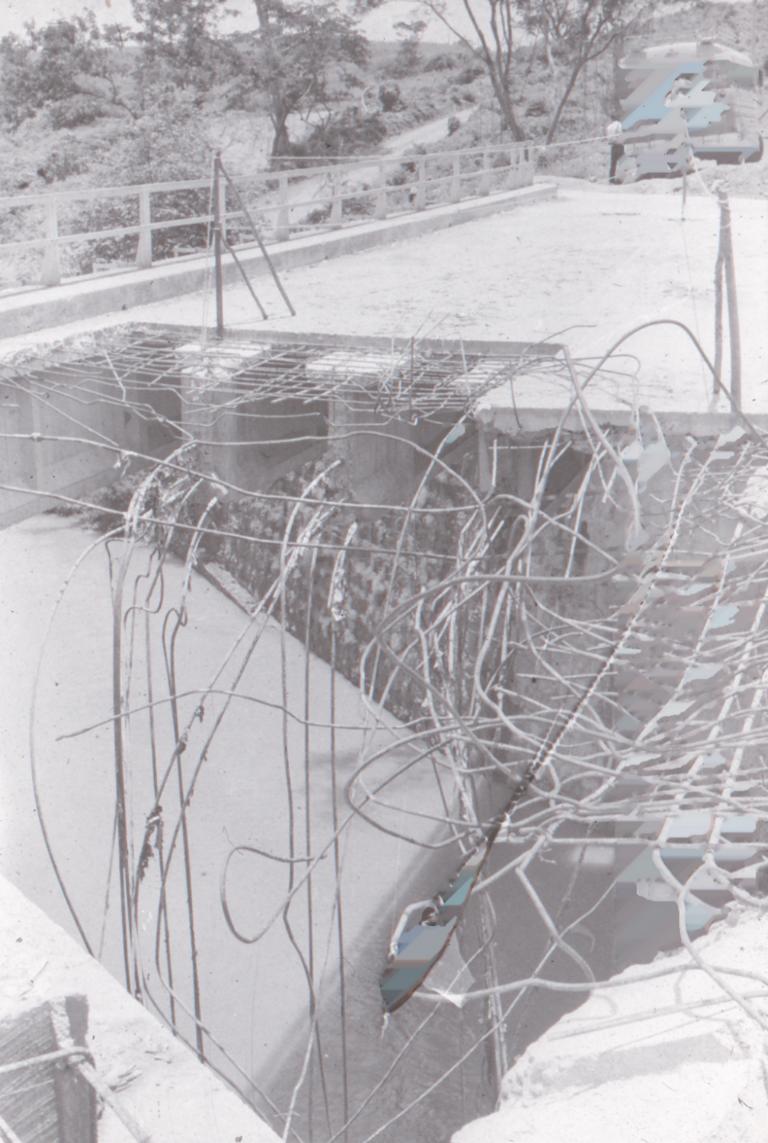

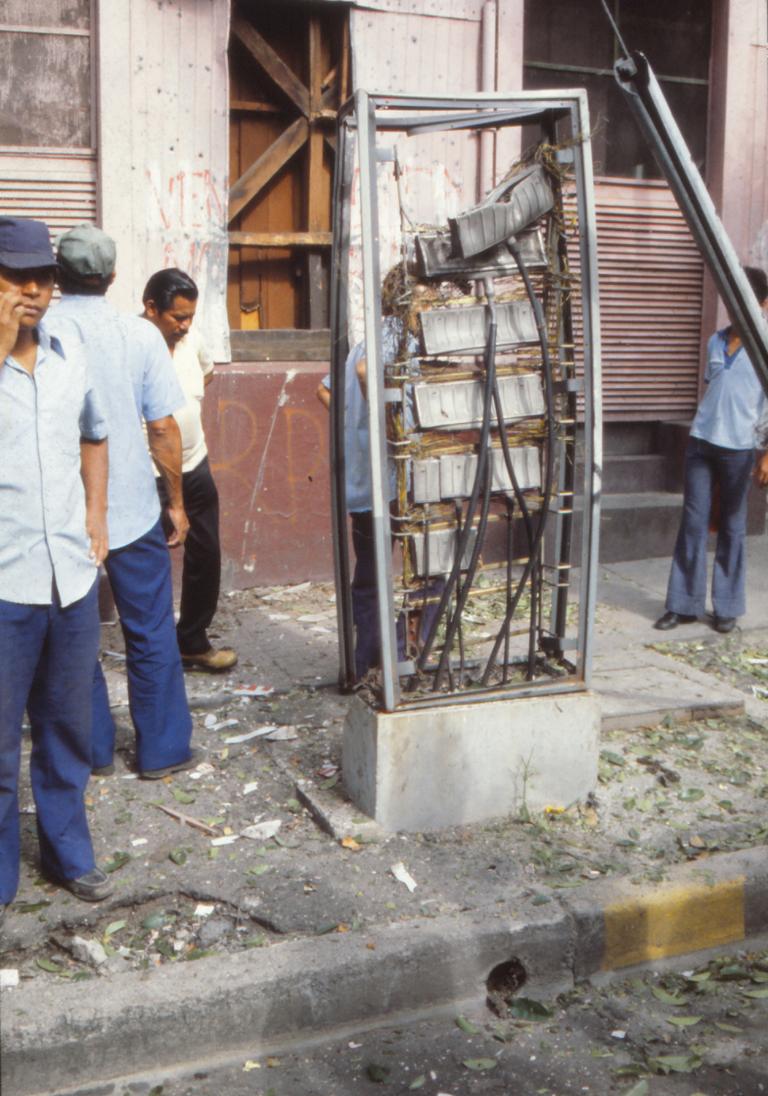

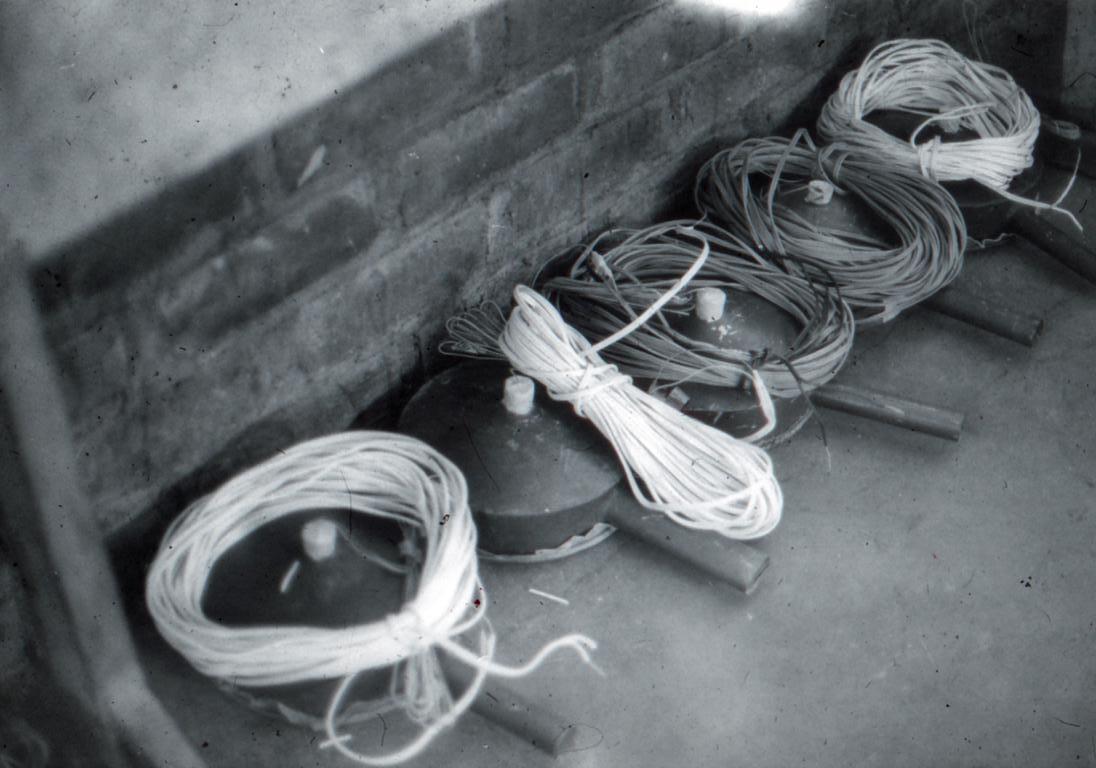

In 1980/1 the guerilla was targeting the countries transport and communication infrastructure. Photos show a bridge on a road leading to Chalatenango and telephone communication equipment blown up.

The war started in 1980 when civil protests turned into armed resistance. It is remarkable that the FMLN guerrilla in such a tiny country for 12 years successfully resisted the Salvadorian army which had been heavily training and equipped by the USA. Asked how the guerrilla was able to survive without large and secure areas of retreat one of the commanders told me: “The people were our forest”, meaning that the support by the population in the liberated areas was so strong that the guerrilla was able to hide whenever needed. This also explains the large number of civilians killed by the army in various massacres.

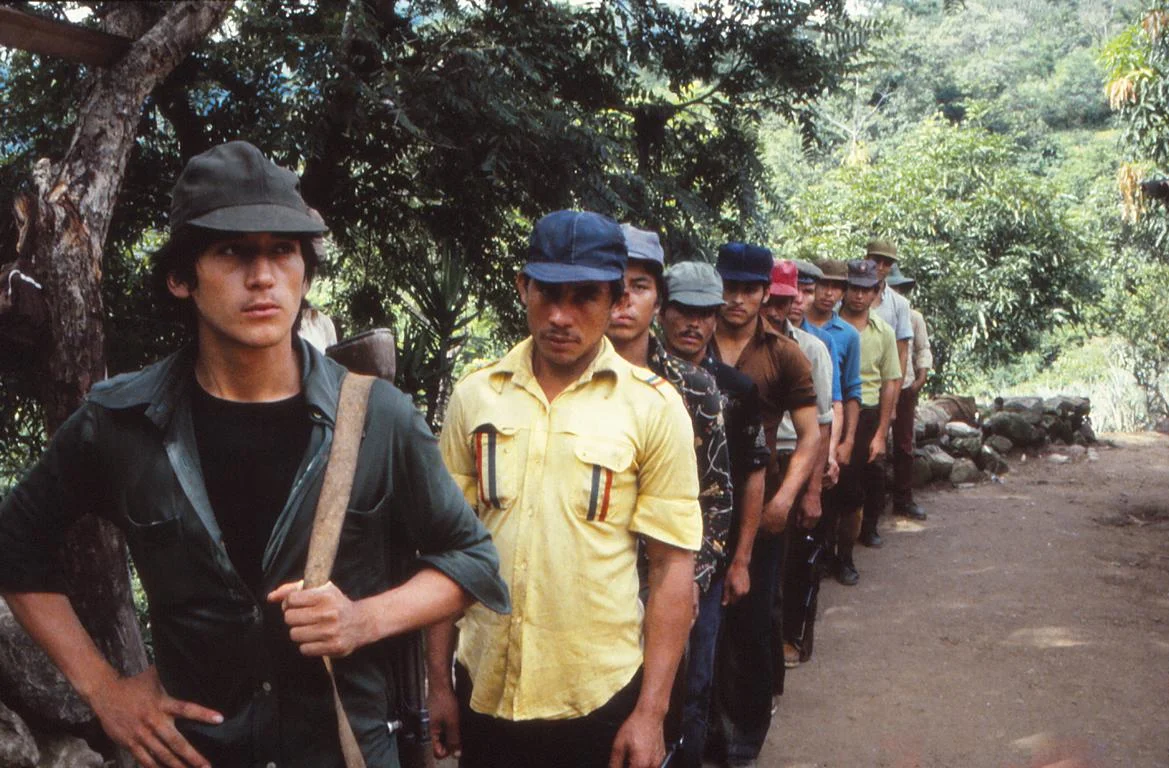

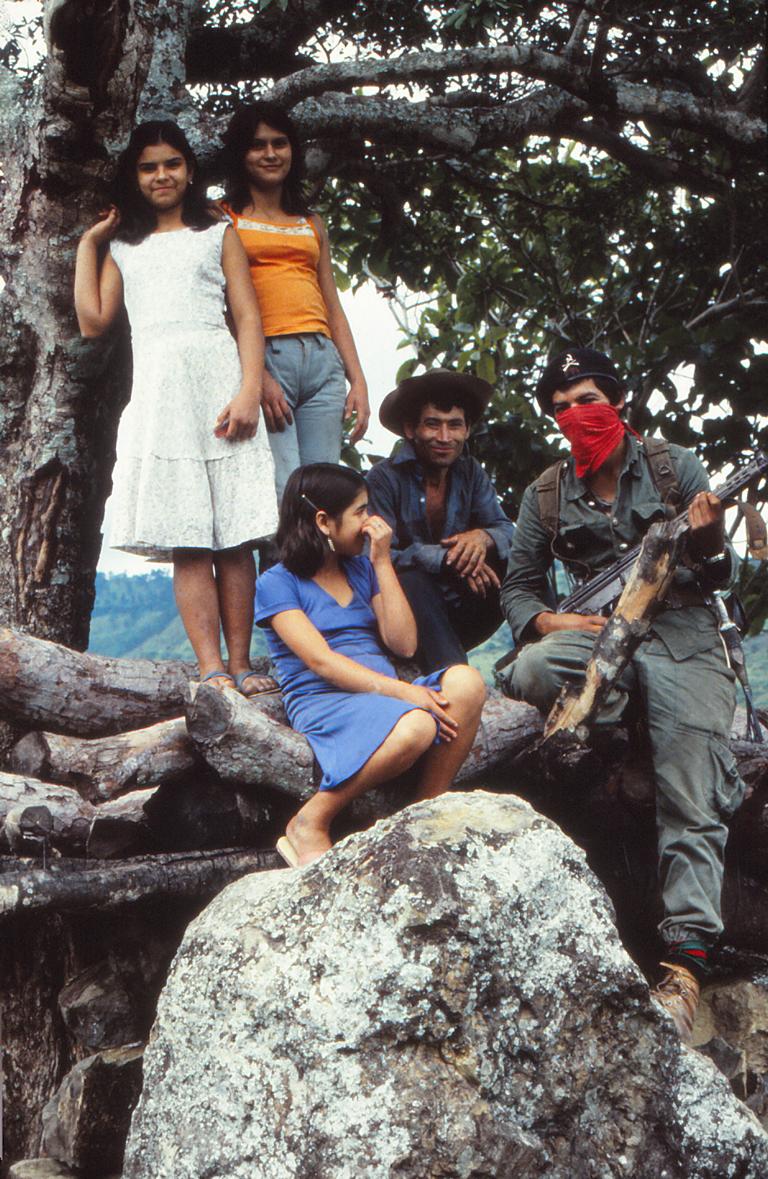

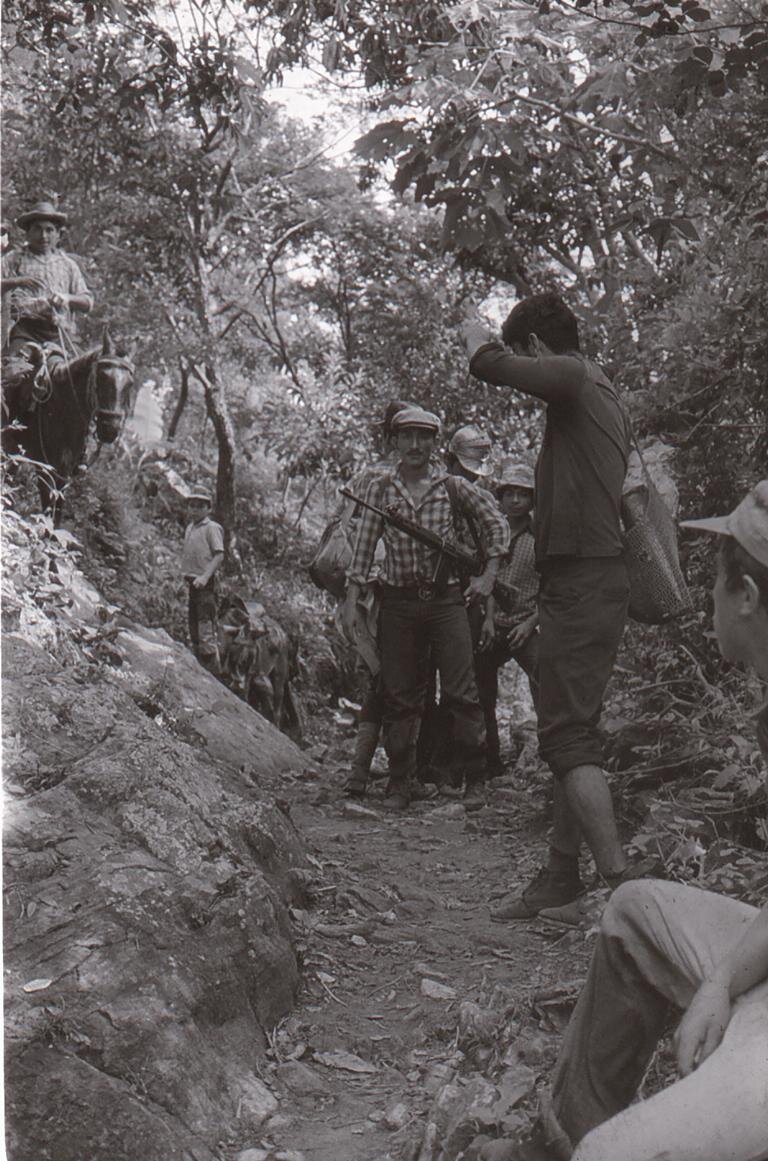

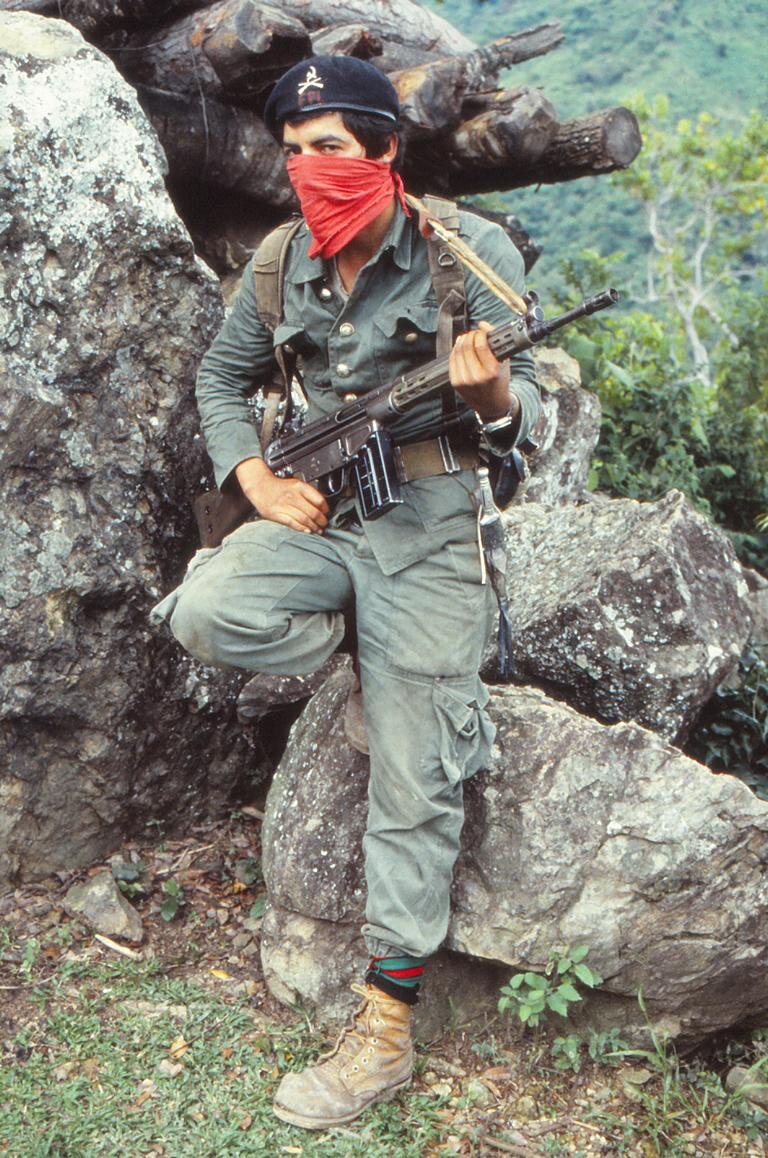

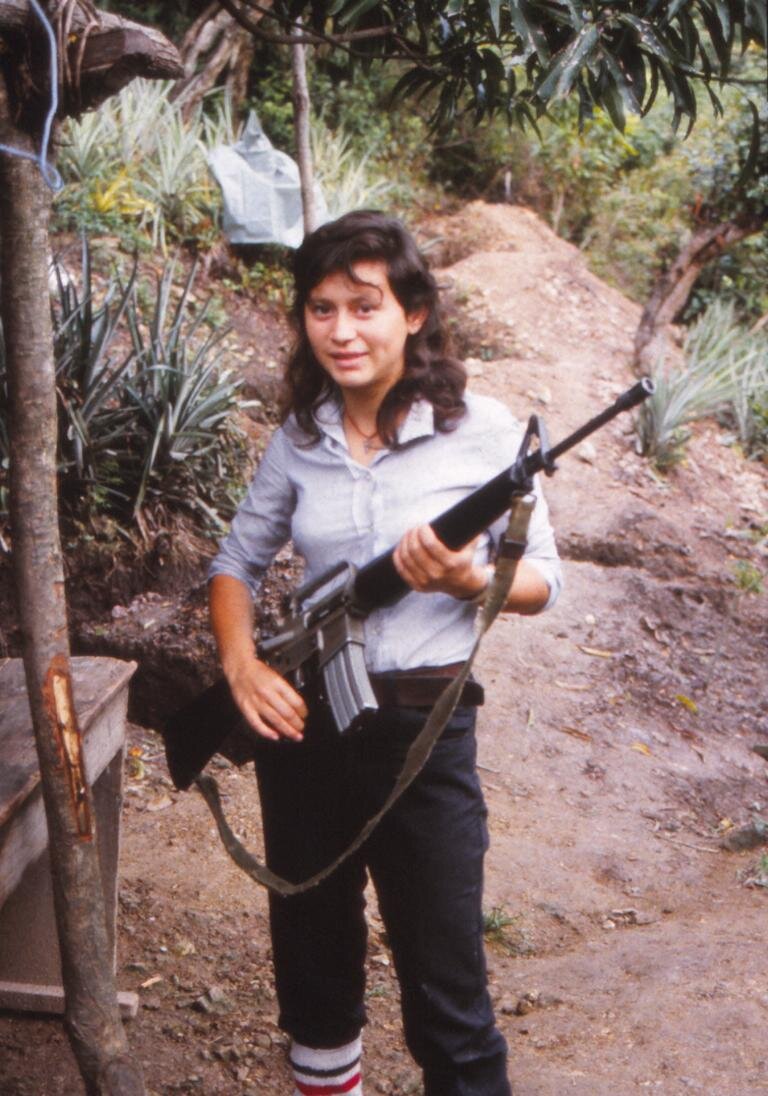

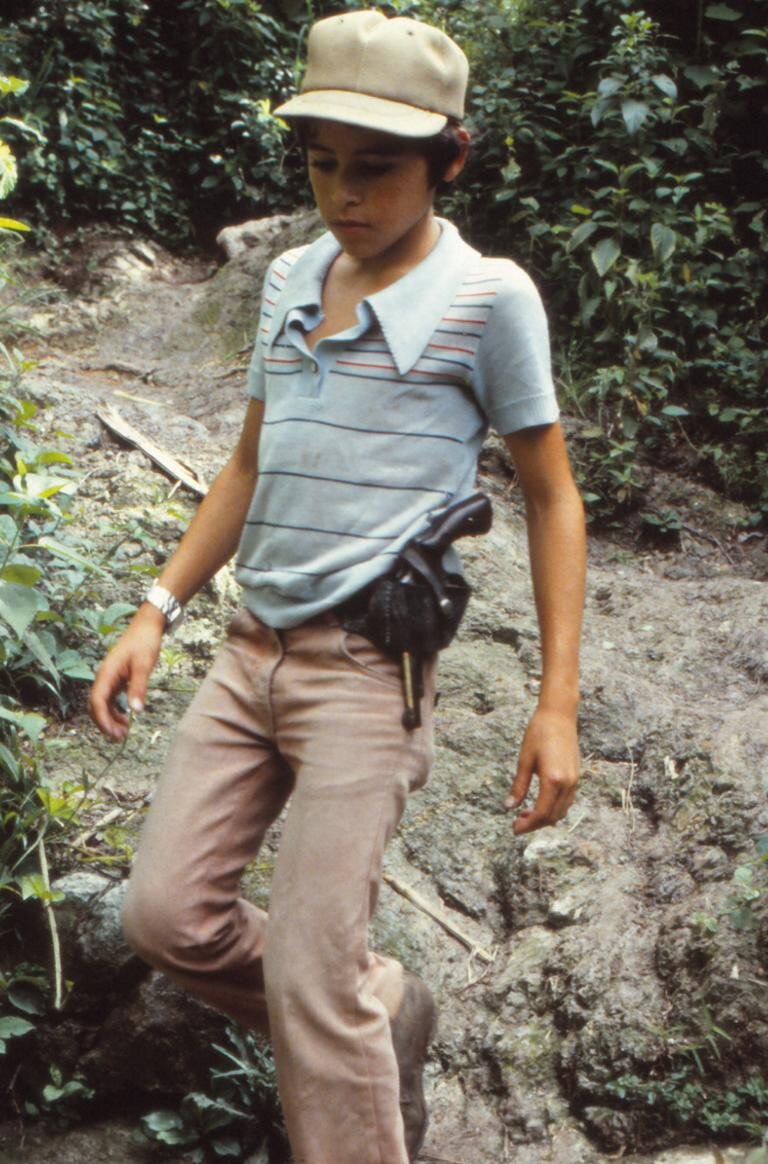

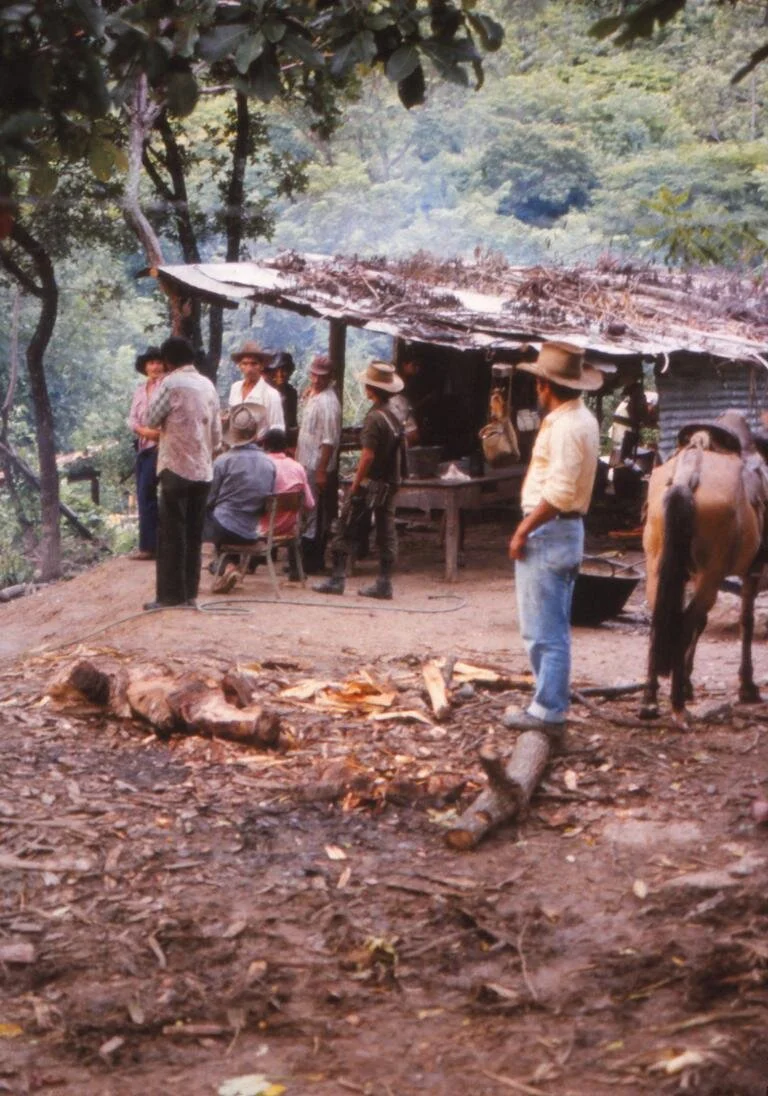

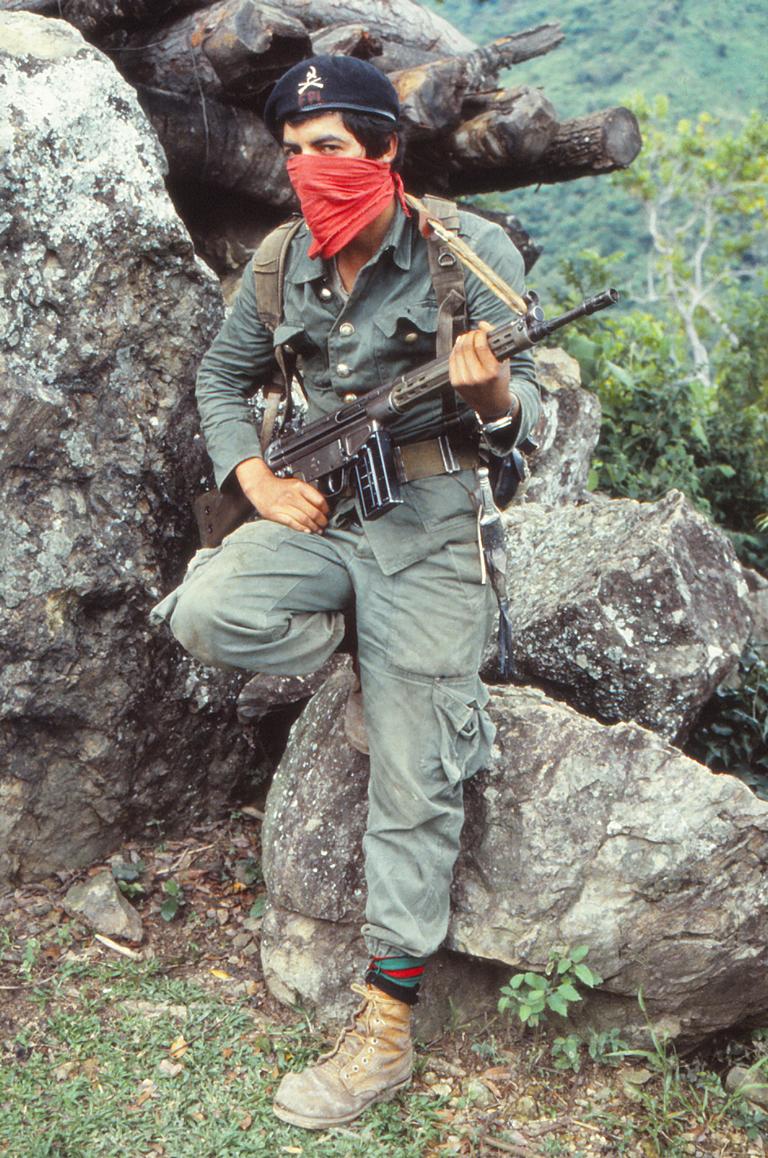

The story that all journalists were after was to stay some time with the guerilla in the mountains. Problem just was that it was quite risky to cross from one side to the other. In 1981 I was arrested together with a German journalist and a guide from the guerilla by a military patrol when heading towards the mountains. We were kept in prison for a day until we finally were able to talk our way out of captivity (we had already a story prepared in case we would be detected). A week later we tried again and this time managed to reach the guerilla camp in El Jicaro / Chalatenango where we stayed for a week. Photos show the area of El Jicaro and members of the guerilla.

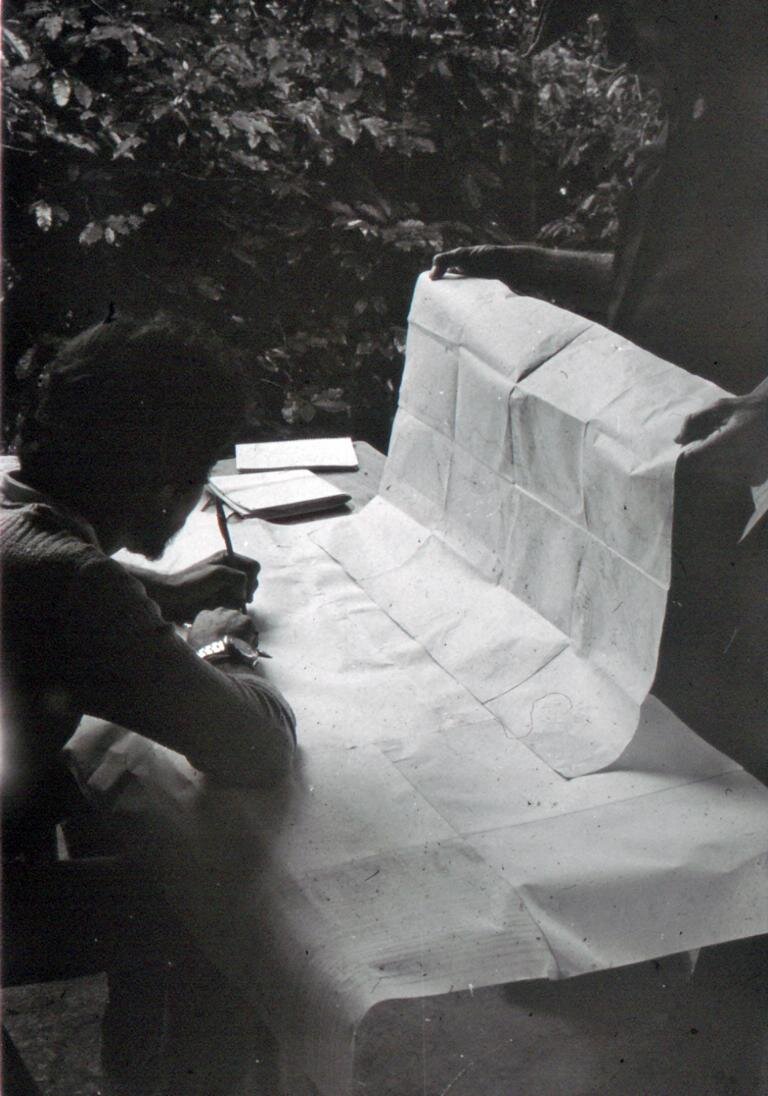

In 1981 the guerilla was still in the build-up. The weaponry basically consisted of assault rifles and self-fabricated explosive devices. Maps were hand-copied. Also the trenches, tramps and a tunnel in case of an air attack were quite improvised, but the "muchachos" tried to make the best out of what they had. In order to be useful I repaired one of their out-of-order guns which was highly appreciated as the guerilla was terribly short of weapons. Partly they used the FAL / StG 58 which I had been trained on during my military service with the Austrian army.

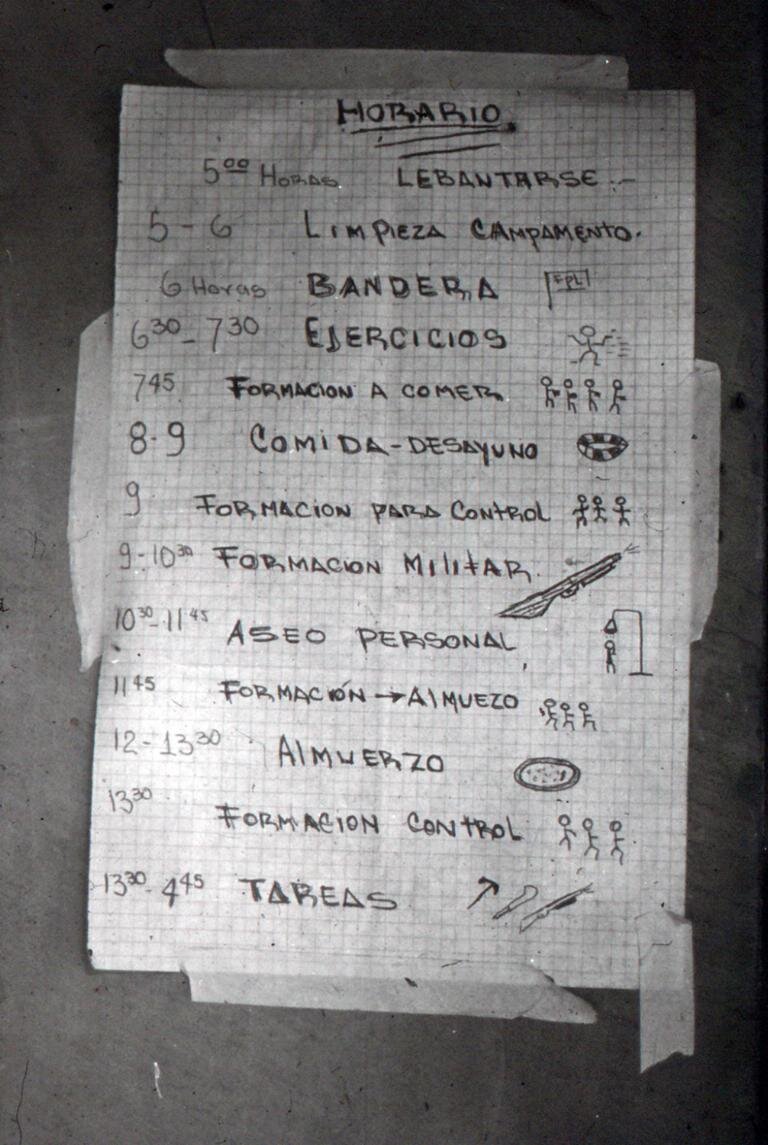

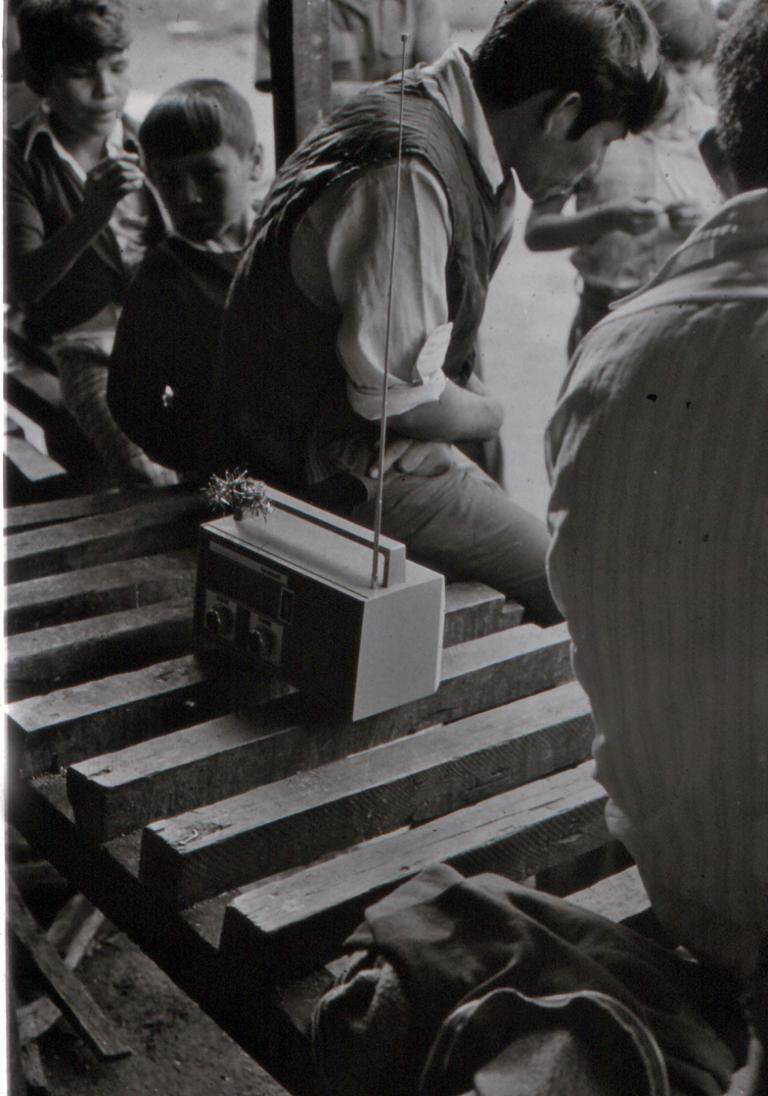

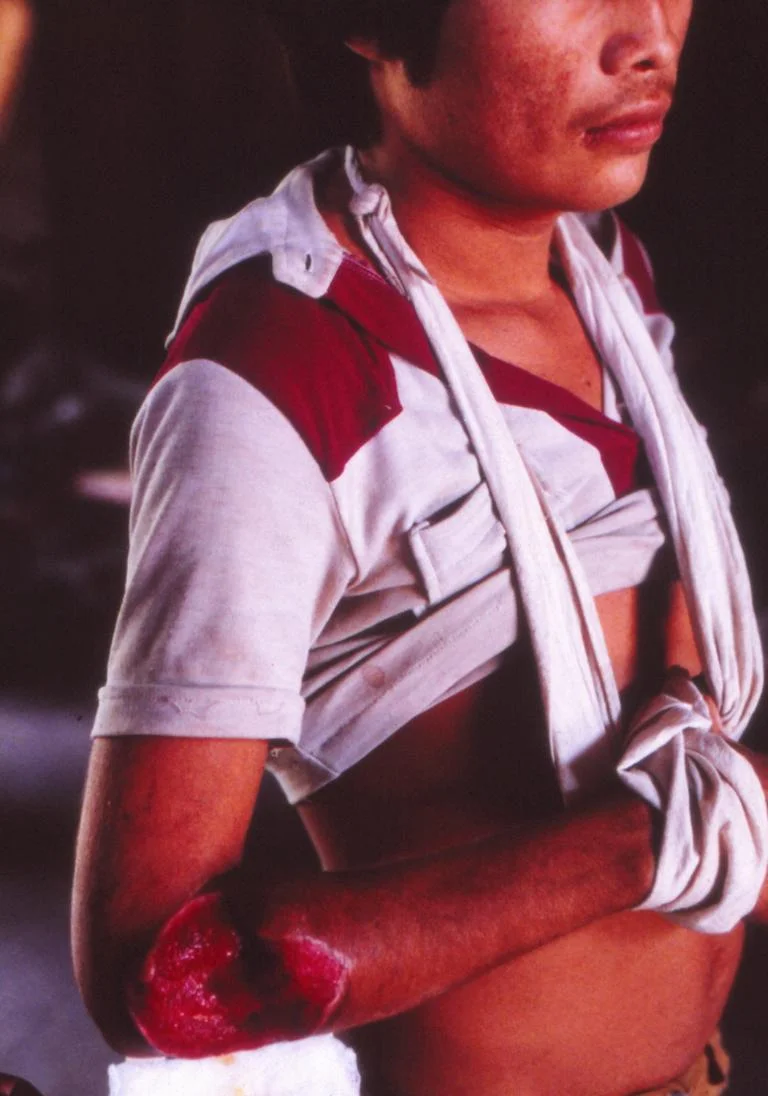

The daily routine started at 05.00 in the morning and included cleaning the camp, physical exercise, military training and works to improve the defense of the camp. There was a lazaret where several wounded fighters were treated. My "medical problems" were much smaller, I was struggling with infected flea bites – the rest of my body looked similar as my right arm. In the evening we were listening to Radio Venceremos, the radio station of the FMLN guerilla, which operated out of one of the liberated areas.

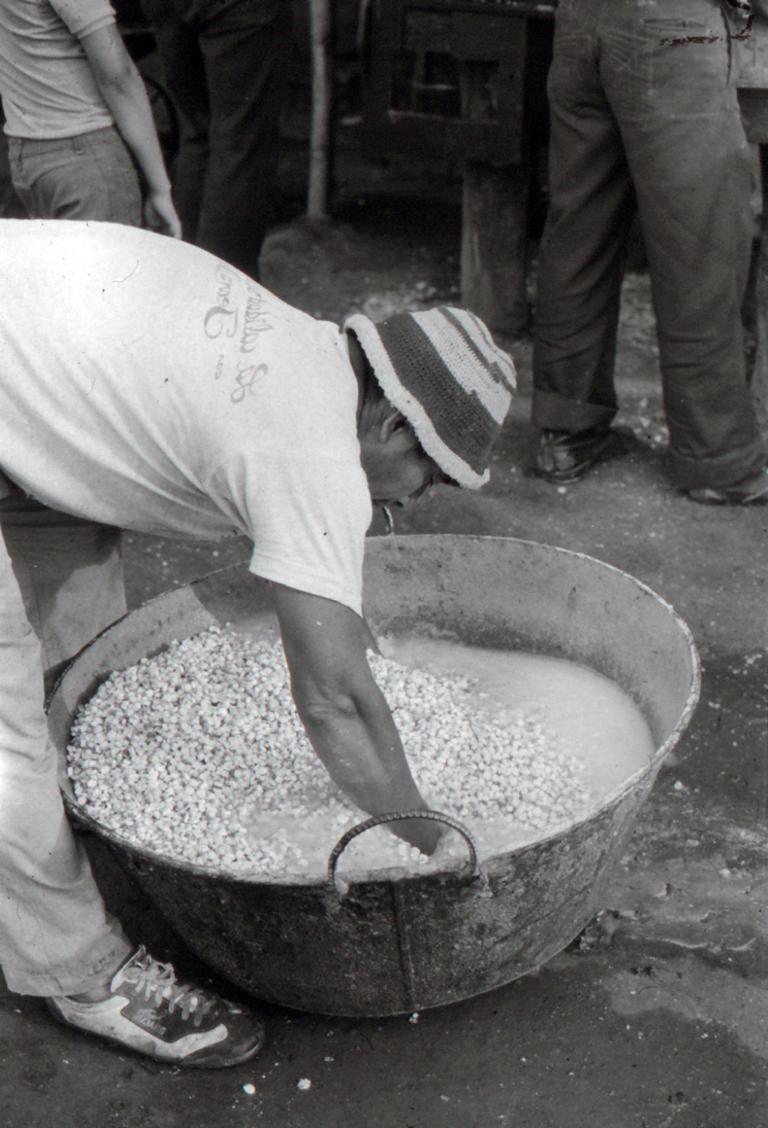

Around the camp agricultural production continued as normal. Commonly seen were sandals made out of old car tires.

Epilogue:

The war lasted until 1992. A military stalemate established in the late 1980s and the end of the cold war opened the door for an UN supported peace agreement (16 January 1992, Chapultepec Peace Accords) which ended the hostility and provided the guerilla movement FMLN the possibility to transform into a political party. Between 1989 and 2004 ARENA (Nationalist Republican Alliance), a right-wing populist party which had been established in September 1981 by Roberto D'Aubuisson, the notorious leader of the death squads, won the presidential elections. In the 2009 and 2015 presidential elections a FMLN candidate was successful.

As part of the 1992 Peace Agreement a UN Truth Commission for El Salvador consisting of independent international experts was established. It released its report "From Madness to Hope" in March 1993 (https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/file/ElSalvador-Report.pdf ) and came to the conclusion that 95% of the atrocities were committed by forces linked to the government and 5 % by the FMLN (see page 36).

The report was rejected by the Salvadorian Minister of Defense as “unfair, incomplete, illegal, unethical, biased, and insolent.” Furthermore, the Salvadoran president, Alfredo Cristiani (ARENA party), claimed that the report did not fulfill the desires of the Salvadoran people who wanted to “forget this painful past.” Five days after the release of the UN commission's report, the government passed a blanket amnesty law impeding judicial prosecution of perpetrators. In 2016 the constitutional court declared the amnesty law invalid and some judicial prosecution of two major cases takes place now.

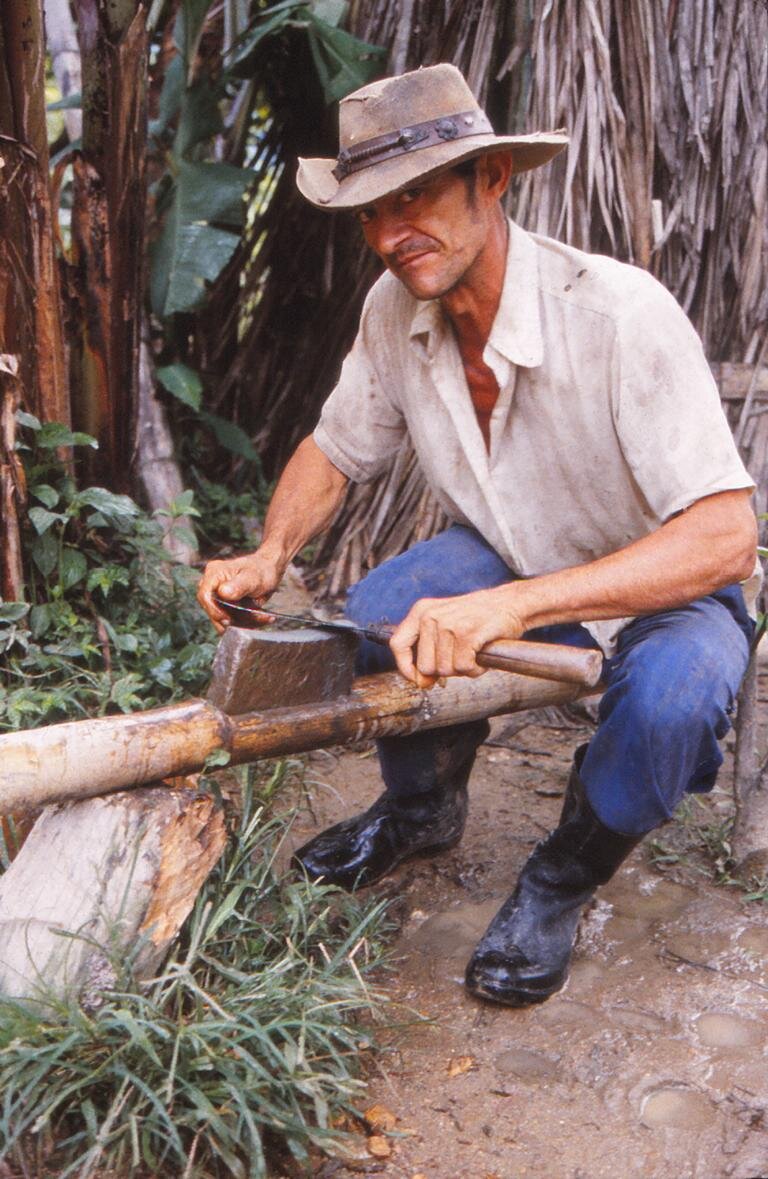

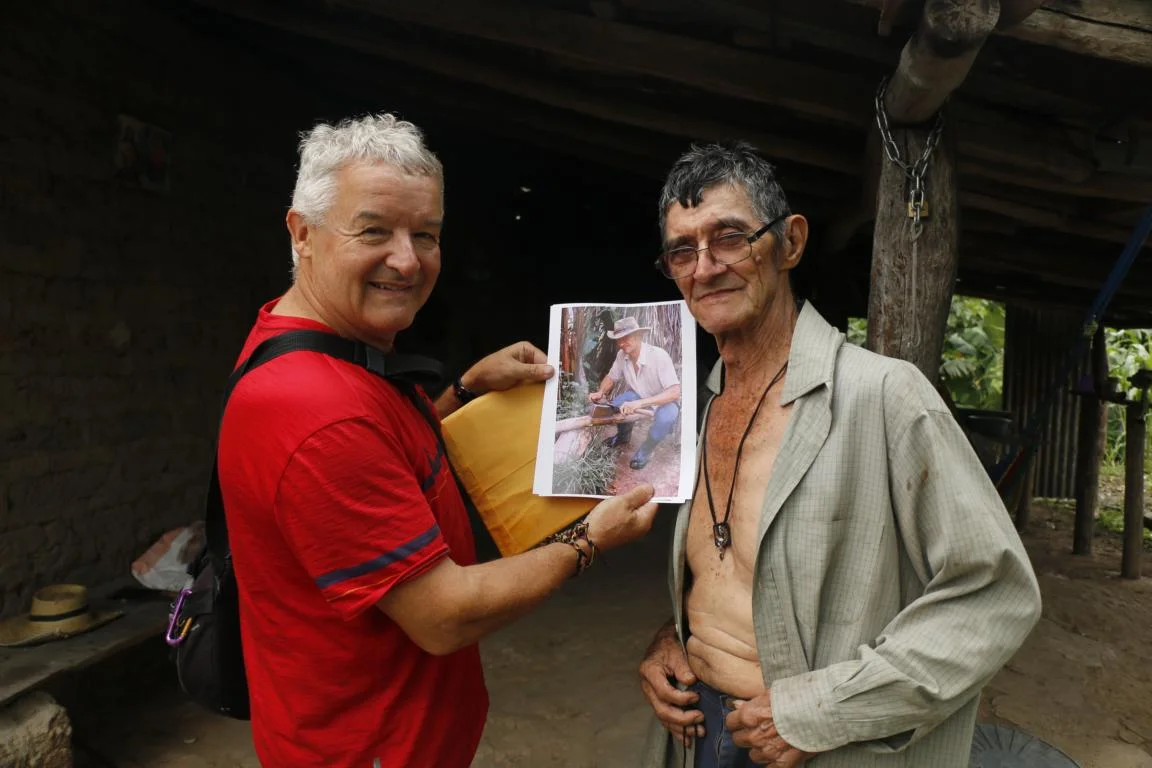

When passing through El Salvador in June 2018 I tried to meet some of the people of which I took photos in 1981. For this reason I returned to El Jicaro / Las Vueltas where I had spent a week in the guerilla camp in 1981. Showing photos to the villagers they in fact were able to identify some of the people on the photos and to inform me about their where-about.

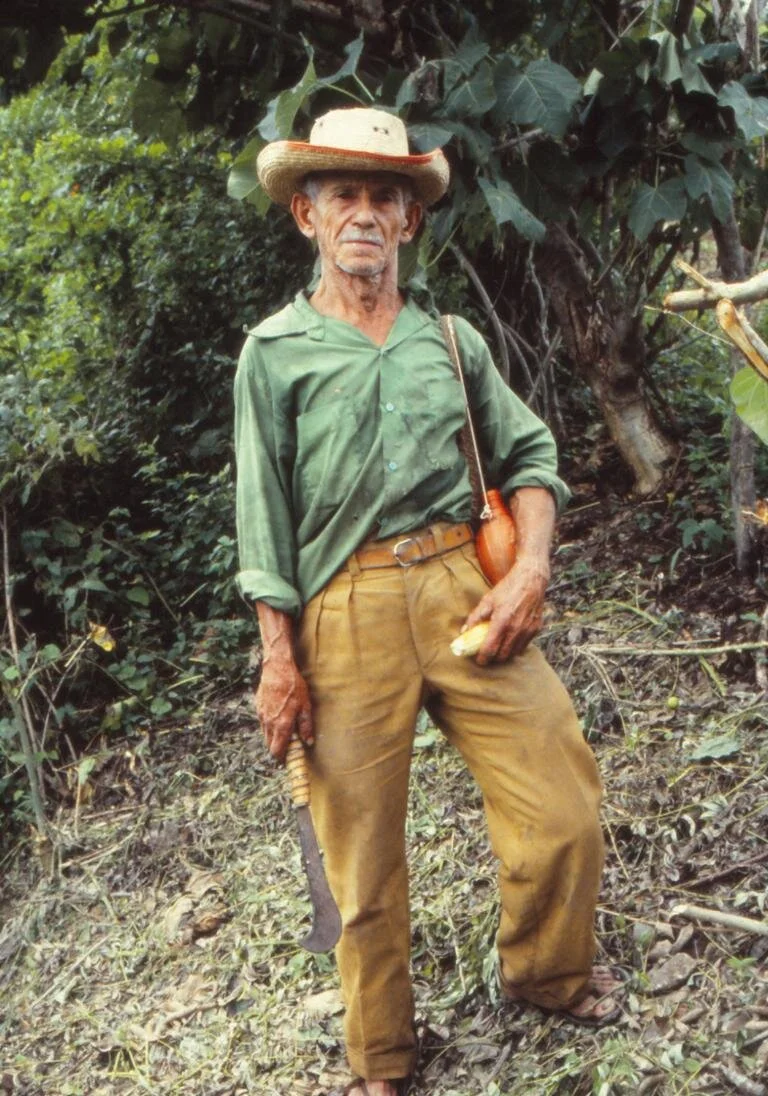

A young man pointed out that the person sharpening his machete is his uncle Luis Rivas who still lives in the village. Luis all his life has worked as a farmer and today is 84 years old.

Roxana Dubon was 17 years old when I took the photo in 1981. Without formal medical education (just being trained on the job by medical doctors and other nurses) Roxana during the whole war time of was working as a nurse treating hundreds of injured fighters and civilians. During the war she got two children (the son has become a medical doctor, the daughter is an architect). Roxana told me that the 16th January 1992, the day the peace agreement was signed, not only was a day of joy for her, but also of fear what will be her personal future with two children and no formal education (the father of her son died during the war in combat as well as two of her brothers). "During the war the FMLN provided me with food, an uniform and boots" she told me, "but with no eduction and two small children what should I live of after the war"? Roxana eventually was able to receive a three-year training to be a nurse and for 20 years is working in the clinic of her home town Arcatao. In one corner of her house she has established her little private museum where she keeps items of her time in the mountains, including her M 16 rifle (which has been cut and rendered unusable). She truely is a remarkable women.

Filipon Vidareno was severely wounded in summer 1989, when a bullet hit his leg. With assistance of the Red Cross he was transferred to a government hospital where he was confined and received medical treatment for 11 months. He told me that "as all others I doubted whether or not I would survive the war. We lived just from one day to the next". Looking back he stated "that the main problem which led to the war - the social injustice - still is not resolved. However, it is a big step forward that as a result of the war we are now in the position to apply peaceful and democratic means to fight for our interests".

Still suffering from consequences of his injury today Filipon works in the maintenance at the airport of San Salvador. Being 58 years old Filipon as many other FMLN fighters faces the problem that it will be difficult to receive a pension. The FMLN did not succeed that the time in the guerilla would count for the 25-year minimum period necessary to be entitled for a pension.

In Las Vueltas I also met Maria Dolores and her husband Rao. Both were among the few who survived the massacre at the Rio Sumpul in May 1980 as they were able to run across the river fast enough to escape the killing. Rao later joined the FMLN and during the war was in charge of logistic in the area of El Jicaro.

Eventually now I was also able to take pictures of the military base “El Paradiso” (“the Paradise”) where we were kept as prisoners in 1981 for one day. Funny enough when working in Bosnia in 1996 for the Organization for Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE) I had an American supervisor who had been a US-military advisor in El Paradiso (however not at the time of my detention). It is a small world….